Ducal Palace of Medinaceli

Soria

The Plaza Mayor of the town of Medinaceli, in the province of Soria, the original site of the Ducal House and head of the state of the same name, is dominated by this palace built in the first third of the 15th century and extensively renovated in the first quarter of the following century by the king's chief architect, Juan Gómez de MoraIn 1623, Juan Luis de la Cerda commissioned the work from Juan Luis de la Cerda, VII Duke of Medinaceli, in a project that also included the aforementioned square and the collegiate church of Santa María de la Asunción.

On 11 February 1622, Francisco del Águila, administrator general of the estates of the Duke of Medinaceli, appeared before the corregidor of the town of Medinaceli, to declare that ".the main houses which is the palace of the lords of this house situated in this town are all devoured and especially the front and the coredor of the main courtyard of the bentanaje and the rooms inside and all in a way that threatens very great ruin.." (ADM, Medinaceli, 42,21)

The ruin of the old palace was the occasion for the VII Duke of Medinaceli to transform his façade, staircase and courtyardIn 1623, he commissioned Juan Gómez de Mora, master builder to King Philip IV, to draw up new plans for the building, giving it its current appearance.

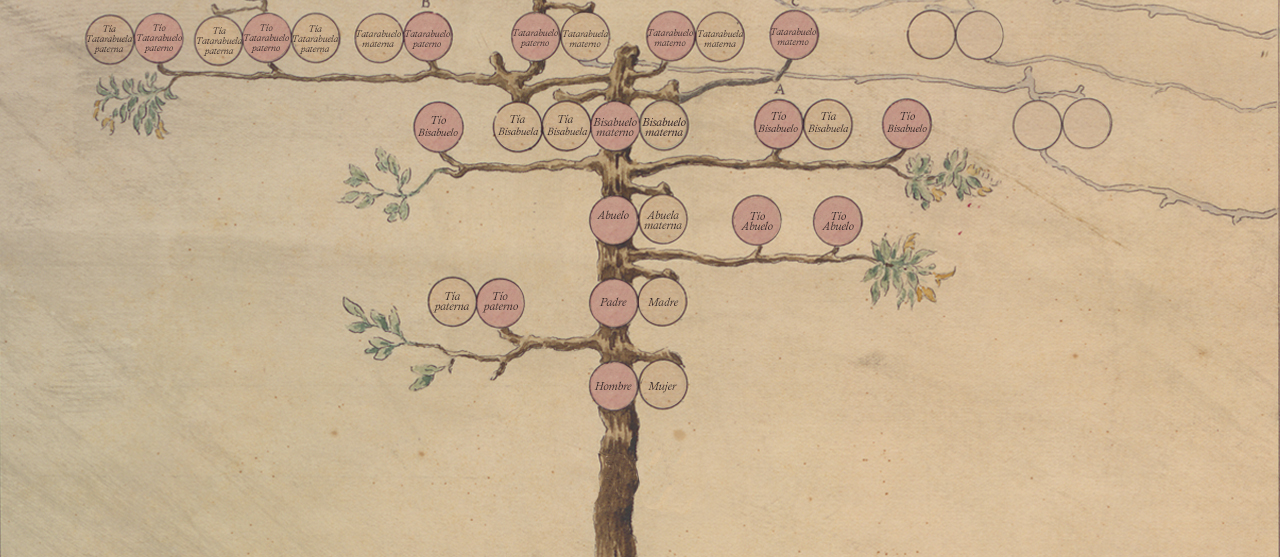

The primitive palacecalled "NEW PALACES"in a document of 1435 (ADM, Medinaceli, 102, 3). must have been built by the 3rd Count of Medinaceli in the first third of the 15th century.possibly close to the marriage of his son Gastón de la Cerda to Leonor de la Vega y Mendoza, daughter of the 1st Marquis of Santillana, celebrated in 1433. These "new palaces"The palace served for a very short time as the main residence of the Counts of Medinaceli, as at the end of 1480 the 1st Duke of Medinaceli built a new palace in Cogolludo, which took over this function for eight generations. The The new government, with the functions of representation and administration of the seigniorial state of which it was the head.must have undergone successive alterations throughout the 16th century. The most important and the only one that we can date with some precision is the passageway built around 1556 to connect the palace to the Collegiate ChurchThis date can be deduced from the licence granted by the Provisor of Sigüenza to open a door in the wall of the then parish church - seven years later a collegiate church - of Santa Maria de la Asunción. Other alterations can be deduced from the 1622 works dossier mentioned at the beginning, as, for example, it proposes to demolish the main façade "...".more than for the little strength it has at present is because in the said front the windows have been changed and now it has them again, of which the breaks are visible and the windows have to be changed again to put them with the same distance. "

Antonio Juan Luis de la Cerda, 7th Duke of Medinaceliwas the son of Juan de la Cerda y Aragón and Antonia de Toledo Dávila y Colonna. His father died just a few days after his birth, and his mother was still a minor, was left under the guardianship of his maternal grandfather, Gonzalo Gómez Dávila, 2nd Marquis of Velada, who at the time was Philip III's majordomo mayor, a character who has been defined as "a nobleman inclined to architecture as entertainment and as a resource for his political and social projection"It was he who promoted Francisco de Mora, one of the greatest representatives of Herrerian architecture, to the office of aposentador de Palacio and maestro mayor de las obras reales, whose masterpiece is the palace complex which, in his villa of Lerma (1601-1617), was sponsored by the famous valide of Philip III, paternal great-uncle of the VII Duke of Medinaceli. This work and the two offices mentioned above were inherited by Juan Gómez de Mora on the death of his uncle Francisco in 1610.

It is in this environment, where architectural culture is considered an essential part of aristocratic learning and royal patronage of architectural works, that Antonio Juan Luis de la Cerda was educated and, at the age of 16, wanted to show the lessons learned in the reform of his Palace of Medinaceli, not with the purpose of improving its quality as a dwelling, but, as his administrator of the Medinaceli Estates declares, "...to make it a better place to live.because the greatness of the house, being the head of this state, it is not convenient for it to come [the palace] to such ruin."

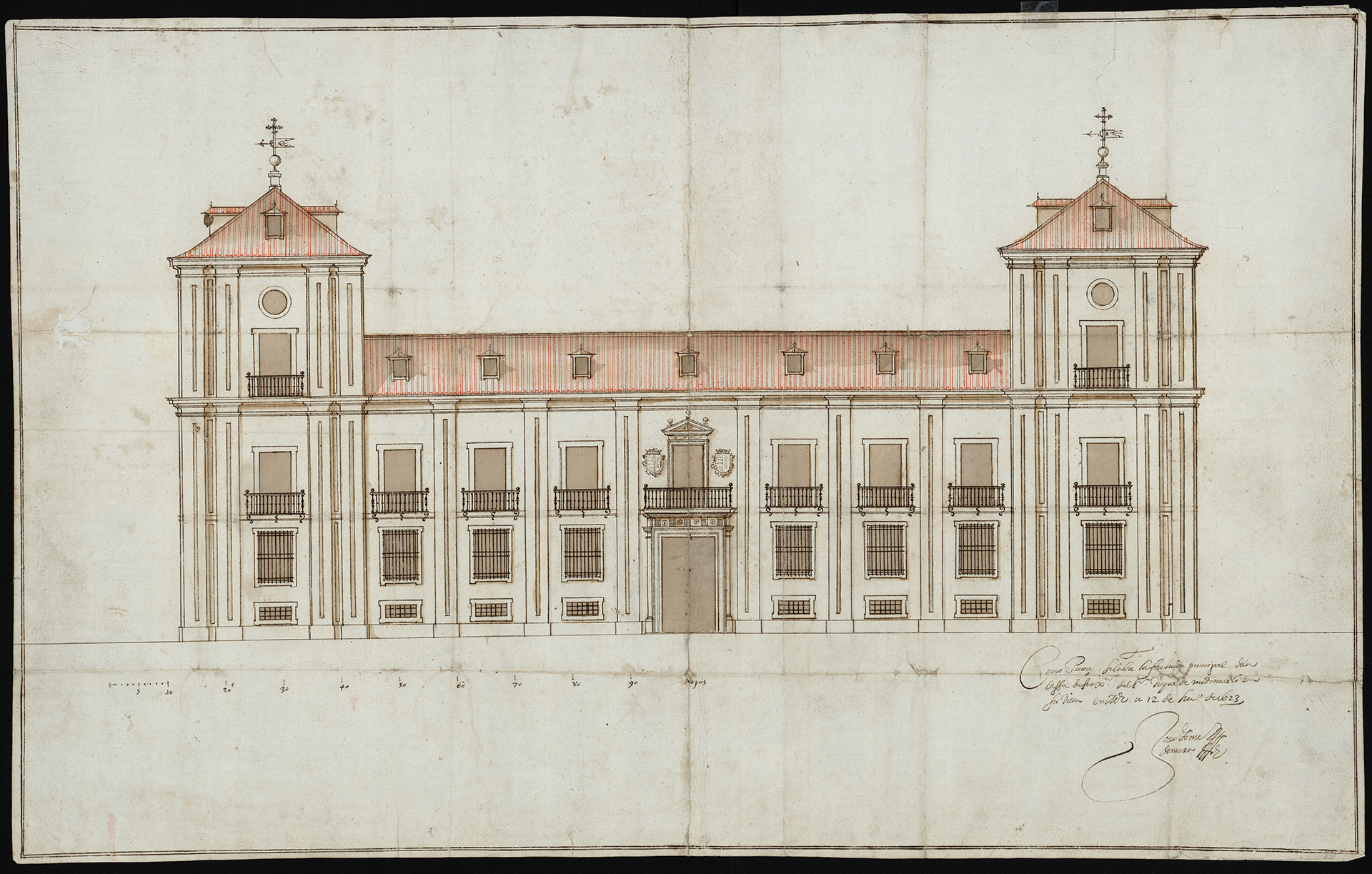

The works affected the entire palace, Gómez de Mora's intervention concentrated on the courtyard and especially on the façade.This is particularly evident in the masonry moulding of its fenestration, in the grandeur that its high angular towers were intended to give it, and in the rhythm given by the succession of massifs and hollows, a rhythm reinforced by the alternation of colours that a document from 1735 describes as masonry, red brick and masonry boxing, making clear that the design which Gómez de Mora drew and coloured in the traces of 1623 -which are signed with the following annotation "Como parece se labre la fachada principal de su exª del Sr. duque de Medinaceli en su Villa, en Md a 12 de henº de 1623", was scrupulously respected. In the rooms, the intervention was more limited, focusing on the restoration of the plasterwork, coffered ceilings and polychrome alfarjes.

Elevation of the façade of the palace of the Dukes of Medinaceli in the town of the same name in Soria. Juan Gómez de Mora, 1623

The work on the palace was part of a joint intervention plan that included the Plaza Mayor of the ducal villa and its surroundings and the remodelling of the collegiate church.

Antonio Ponz, in his Viaje de España, when he arrives at Medinaceli, says: "It is the estate of the Duke of Medinaceli, whose palace is of better architecture than the one H.E. has in the Court, although it is small. The door and windows are of good shape and proportion. It is a building worthy of conservation and restoration in several parts [...] The chapel is spacious with a painting by El Greco on the altarpiece, of a strange composition in which he represents the Prayer of Christ in the Garden..."

The deterioration, of which Antonio Ponz had already warned, continued throughout the 19th century, although at the beginning of the 20th century, a photograph in the Espasa encyclopaedia shows that the façade was fully preserved. During the Civil War it suffered a great deal of damage and presumably lost its two towers, a deterioration that continued afterwards, when the Foundation received it in 1978, it was in a rather dilapidated state.. By agreement with the Junta de Castilla y León in 1995, the ground floor was ceded to the town council of Medinaceli. and the most urgent rehabilitation and consolidation work on the palace was discussed with joint funding from both institutions. In 2008 the municipality of Medinaceli signed an agreement with the DeArte Foundation.Since then, the institution has maintained a permanent exhibition on the ground floor and tries to revitalise local life through various cultural activities, for which it promoted the covering of the courtyard with a superb glass dome.