History of Tavera Hospital

This building construction began in 1540commissioned by the Cardinal Juan Pardo Taveraand was in the works until 1624. However, understanding its architecture and uses requires both going beyond this already long chronological framework and analysing not only the will of its founder, but also, and perhaps fundamentally, that of the executors of its assets and its memory.

The history of this building is covered here, beginning with the ideological context in which the cardinal-archbishop conceived the uses, welfare and funerary, that determined its architecture and ending with the process leading up to its current uses as an immense cultural continent. This history is divided into periods, which you can access by clicking on each date on the chronological axis below, indicating their beginning. The interested reader can read Fernando Marías's book, entitled The Tavera Hospital in Toledopublished by the Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli in 2007.

A new approach to health care

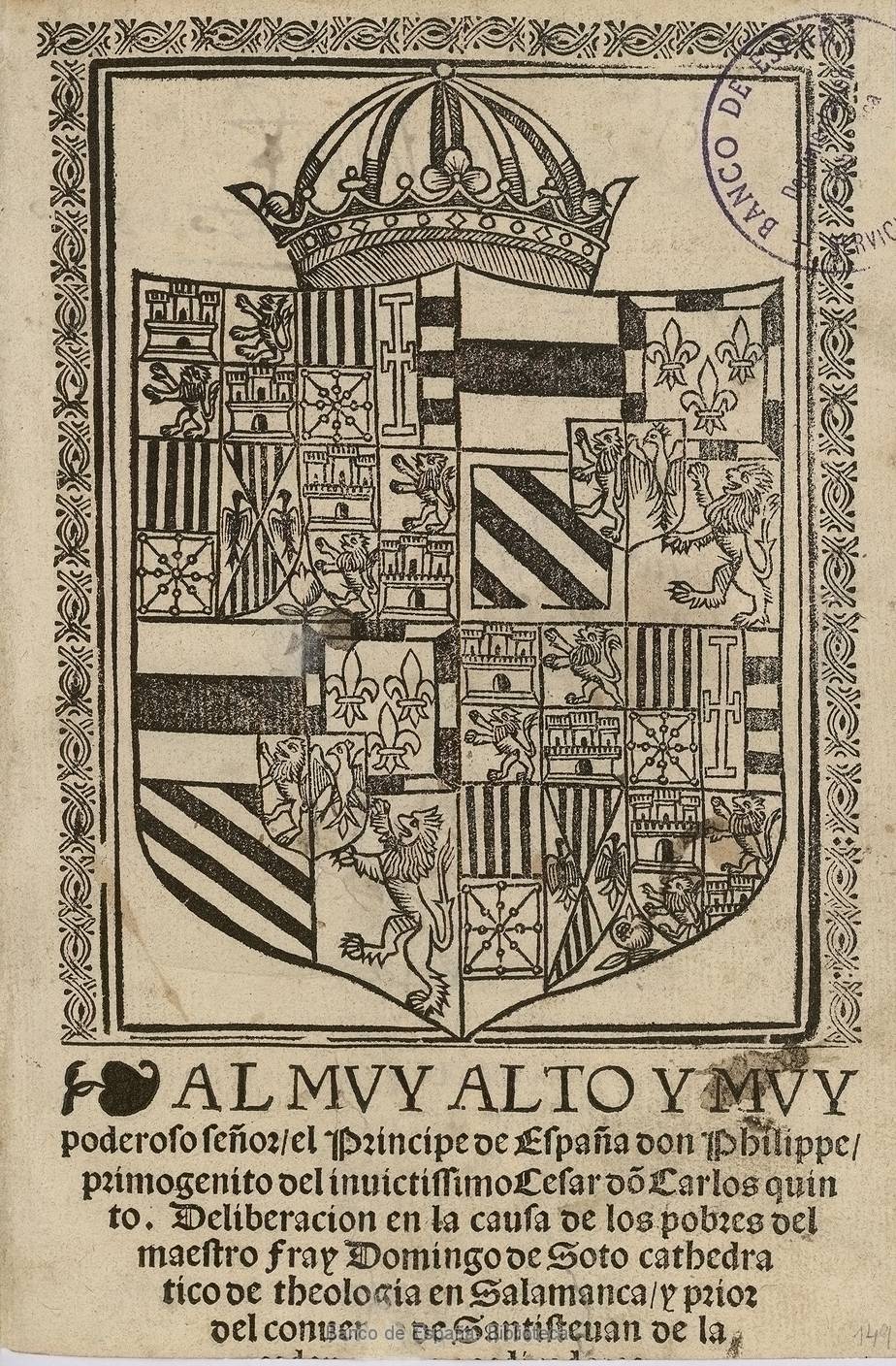

Cover of Domingo de Soto's book "Deliberation in the Cause of the Poor" published in Salamanca in 1545 and dedicated to the then Prince Philip. A few months earlier, in Valladolid, Cardinal Tavera had asked this Dominican professor and the Benedictine preacher Juan de Robles to write on the "cause of the poor" and submit their opinions to him. It is in the context of this intellectual debate on poverty, the most rigorous in 16th-century Europe, that Cardinal Tavera's decisions on the functions and uses of his hospital foundation were made.

Although it seems clear that Cardinal Tavera founded this hospital, under the patronage of Saint John the Baptist, as a monument to his memory, it is no less evident that he wished to link it to an institution organised in accordance with the new social ideas with Erasmist roots which circulated at the court of Emperor Charles V and which proposed, from a a new approach to healthcare, begging and charityto dedicate hospital institutions exclusively to the care of the sickdispensing them from their medieval function of sheltering the poor. In this respect, although historiography is right to point out, in founding this hospital, Cardinal Tavera's possible intention to emulate the great Cardinal Mendoza and his hospital of Santa Cruz, it should be remembered that the intellectual context in which he founded it - and which conditioned its architecture - was completely different, and that he finally renounced burying himself in the primate cathedral like the former, giving his foundation a new function as a pantheon, which once again affected its architectural physiognomy.

When the Cardinal conceived the idea of founding a general hospital, he was already a man in his sixties and had just been named Inquisitor General and to step down as president of the Council of Castile, an institution that Charles V called the "the pillar of my kingdoms". Having passed through all the ranks of the civil and ecclesiastical cursus honorum, he had reached the height of his power. After the death of Empress Isabella in May 1539, when the Emperor announced that he was leaving Castile again to put down the rebellion at Ghent, he left the nominal regency to his son Philipa twelve-year-old boy, and the effective governance who was the most important personage at courtthe Inquisitor GeneralHe received instructions and powers similar to those that the Empress had had as regent years before.

No one in Castile had more knowledge and power than he did to addressing a long-standing problem The problem that, from the beginning of the 16th century, had taken on new proportions: the capacity of the cities to assimilate the flow of people that the cyclical agrarian crises expelled from the countryside. In the 16th century, the problem of poverty was primarily an urban issue which was of particular concern to the patricians of the major cities. As president of the Cortes, Cardinal Tavera had often had occasion to listen to the recurrent request of the representatives of the Cortes to establish measures to control begging and vagrancy.

The bad harvests of 1539 had aggravated the problem: in March 1540, the Cardinal wrote to the Emperor "...".Across the country there is little bread and in some provinces none at all."In the following summer, he enclosed a memorial on the measures to be taken in Madrid for the relief of the poor. Charles V responded by approving what had been done and encouraging him to overcome the "difficulties" that would arise from introducing in the kingdom some new social assistance measures which, for twenty years, had been spreading throughout European cities, from Nuremberg (1522) to Genoa (1539). These measures were endorsed by thinkers of the stature of Juan Luis Vivesa humanist very close to Thomas More and Erasmus of Rotterdam, who, in 1526, in Bruges, published a work titled De Subventione Pauperum in which he defended these measures for the secularisation of beneficence, which, despite some scandal among the mendicant orders, had a great influence and spread. Some ordinances, such as that of Ypres, served as a model for the Imperial Edict of 1531, which extended the new poor policy to all the cities of the Low Countries.

The emperor's encouragement spurred the cardinal to act in a twofold direction. In his governorshipprompted him to enact a poor lawknown in historiography as Tavera Law. This law restricted begging, without actually prohibiting it, and aimed to eliminate it "...".through the proper administration of the revenues of the charitable institutions". Like Archbishop of ToledoIn his archdiocese, and more specifically in the imperial capital, Toledo, he put the new ideas of social assistance into practice. His accounts show that in 1540 he invested 45,000 ducats and 33,000 bushels of wheat in this project. It is in this context that his private initiative to build a general hospital.

Professor Santolaria summarises the content of the social reforms implemented in European cities in four points, three of which are clearly present in Cardenal Tavera's hospital project:

- Centralisation of all charities' aid resourcesThe Cardinal's plan was to merge the small charitable institutions, whether public, private or ecclesiastical, into a general institution. This is the plan that can be deduced from the letter of 5 February 1541, in which the Emperor congratulates the Cardinal and gives permission for him to implement his idea of merging the small charitable institutions of Toledo into a general institution. a single "very spacious and capable hospital, where those afflicted with various illnesses were sheltered".

- Secularisation of the administration of charitable institutions. The Cardinal, by testamentary means, leaves the board of trustees of the San Juan Bautista Foundation, which runs the Hospital, to his nephew, the Marshal of CastileAres Pardo de Saavedra, and not to an ecclesiastical institution.

- Classification or discrimination between the poor and the sick and within the latter, separate them by category: " a special infirmary for the wounded and wounded; and another for the sick with contagious diseases; another for other common and ordinary diseases; and another for the dozen poor sick who have incurable diseases; and another infirmary for convalescents; and another infirmary for the sick who are convalescent."This is the wording of the first draft of the statutes drawn up before the Cardinal's death.

Related content