The Pantheon of the Adelantados Mayores de Andalucía (Pantheon of the Major Adelantados of Andalusia)

Charterhouse of Santa María de las Cuevas, Seville

The chapel and cloister of the Chapter of the Charterhouse of Santa María de las Cuevas today bring together an exceptional group of sepulchral monuments from the House of Ribera. The complex is extraordinary in many ways: for the diversity of sepulchral typologies it contains; for the fact that all the monuments belong to the same lineage; but, above all, for the excellent artistic quality of its two fundamental pieces, the Renaissance sepulchres of Pedro Enríquez de Quiñones and his wife, Catalina de Ribera.

The link between the House of Ribera and the Charterhouse goes back to the person who is considered to be its founder, Per Afán de Ribera the Elderand the context in which this link is generated is that of his promotion, during the reign of Henry III (1379-1406), as a instrument of monarchical authority to pacify Sevillian life, which had been disrupted by the struggles for control of the city between two factions of the nobility led by the Lord of Marchena, Pedro Ponce de León, and the Count of Niebla, Juan Alfonso de Guzmán. He shared this peacemaking role with the official intermediary of the monarch in the conflict, Gonzalo de Mena y Roelaswho, from the bishopric of Burgos, was promoted by Henry III to the archbishopric of Seville in 1394. Two years later, the same king, during his stay in the city, awarded Per Afán de Ribera the Adelantamiento Mayor de Andalucía and, shortly afterwards, he placed the juries of the Seville chapter under his exclusive jurisdiction. The flamboyant Adelantado had held, since 1386, the office of Notary Mayor of Andalusia and one of the twenty-four seats of the Seville chapter, a combination of offices and powers that made him the principal agent of royal authority in the kingdom of Seville.

In that same final decade of the 14th century, the archbishop Gonzalo de Mena carried out two initiatives outside the city walls: the foundation of a hospital for destitute blacks, the seed of the brotherhood of Los Negritos, and the erection of a convent in the fertile plain of Triana around the hermitage that venerated the image of the Virgin of Santa María de las Cuevas, an invocation born, according to tradition, from her discovery, during the conquest of Seville, in one of the caves that the pottery activity created in this plain where the Christians would have worshipped her during the Arab domination. The first cession of this hermitage was made to the Franciscans, to whom it was exchanged for some land in the Aljarafe area, with the aim of handing it over to the order of the Carthusian monks, which enjoyed special protection from the Crown.. In 1400, the first monks from the monastery of El Paular took possession of the hermitage, the first monastery of the order of St. Bruno built in Spain, founded almost posthumously by King John I, so that its development was entirely due to his son, Henry III.

The archbishop hardly had time to organise this new convent foundation, because in 1401 died in Cantillana fleeing the plague that had broken out in Seville. The Great Western Schism complicated the provision of the archbishopric of Seville until 1403, when a consensus was reached between King Henry III and Benedict XIII (Pope Luna) in the person of the man who until then had been bishop of Avila and nuncio of the pontiff in Spain, Alonso de Egeawho, due to his duties before the pontiff, was absent from the diocese until May 1410 (D. Caramazana, 2021, p. 170). Meanwhile, in 1407, the executor of Gonzalo de Mena's will, the canon of the cathedral, Juan Martínez de Victoria, was obliged to hand over to the regent Fernando de Aragón the funds that the prelate had left him for the construction of the Charterhouse, with the purpose of financing the campaign that would culminate in the conquest of Antequera and which would give this future king of Aragon the nickname by which he is known.

The presence in the diocese of new archbishop, who settled in Seville, in 1410, after participating in the Antequera campaign, reactivated the Charterhouse projectHowever, although he had managed to get the pontiff, in 1409, to compensate the order of San Bruno with the royal tercias of some places in the Aljarafe, the difficulty of collecting them prevented them from continuing the construction, at least of their main church, and so they were forced to look for a new protector. Thus, in 1411While burying Gonzalo de Mena in the chapel of Santiago in the cathedral (D. Caramazana, 2021, p. 173), the Carthusians signed a contract with the Adelantado Mayor de AndalucíaPer Afán de Ribera el Viejo, by which he undertook to build the main church of the convent at his own expense and to assign it as an endowment a perpetual income in exchange for the ius patronatus and burial rights for him and his descendants. The work on the church was completed in 1419, according to an inscription that the new patron ordered to be placed on its main arch (Baltasar Cuartero, I, p. 575).

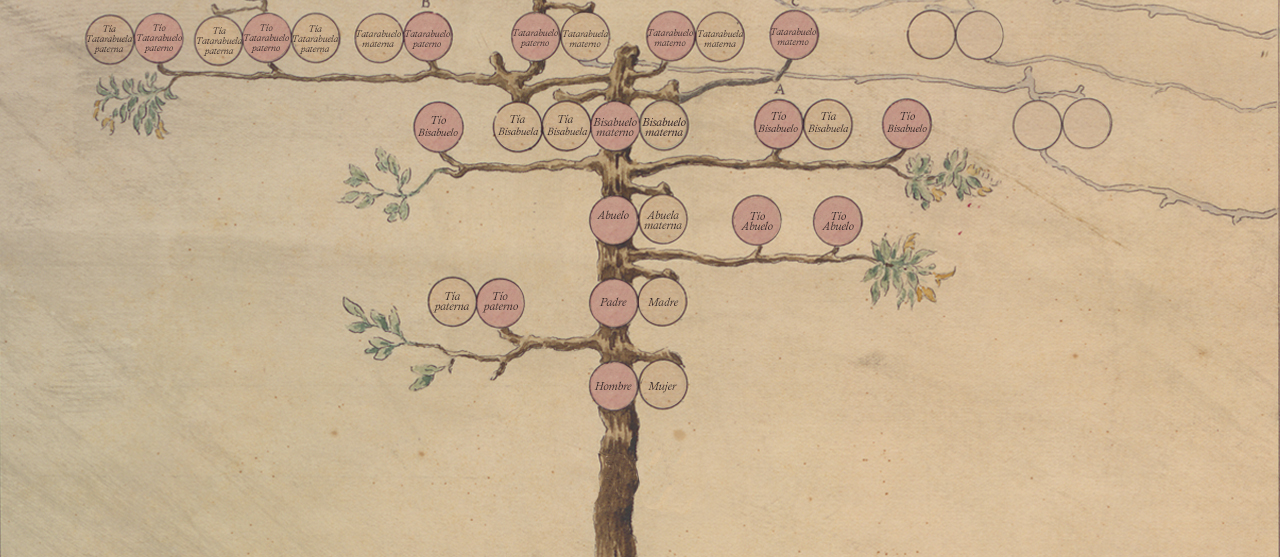

If we consider the very conflictive relationship that Baltasar Cuartero describes in his Historia de la Cartuja between the House of Ribera and the monastic community in the 15th century, it is not surprising that, in 1490The IV Adelantado Mayor de Andalucía, Pedro Enríquez, reached an agreement with the new agreement with the Prior of the Charterhouse by which it obtained, for itself and its descendants, the right of burial in the newly built Chapter House.The most modern building - built in Gothic-Mudejar style - and the most noble - the new community meeting place - of the monastic complex. Don Pedro sought to guarantee a dwelling for eternity for the new lineage founded by his second marriage to Catalina de Ribera, since the first marriage already had the right of burial in the main church, where his first wife, Beatriz de Ribera, Catalina's elder sister, was already buried and where it was foreseeable that his son Francisco, the one called to succeed to the entailed estate of the House and the Adelantamiento, would be buried. However, the latter died in 1509 without succession, so that the first-born son of the second marriage, Fadrique Enríquez de Ribera -better known by the title of Marquis of Tarifa granted to him in 1514 by Queen Joanna- succeeded him in both, so that these two nuclear spaces of the monastery became the mausoleums of a single lineage..

Although we do not know when Don Fadrique first entertained the idea of erecting a series of sepulchral monuments to the memory of his parents and ancestors, certain indications suggest a slow maturation. According to Walter Kruft, the Marquis of Tarifa sought to emulate and surpass the tomb of Bishop Diego Hurtado de Mendoza - the first cousin of his mother, Catalina de Ribera - which Domenico Fancelli had installed in the Capilla de la Antigua of Seville Cathedral in 1510 (1977, p. 330). In 1517, he obtained from Pope Leo X a brief granting "25 years and 25 quarantines of pardon to all the faithful who, having gone to confession and received communion, visit the chapel of the chapter of the monks of the caves, reciting five times an Our Father and a Hail Mary, praying to God for the souls of those buried in the said chapel and for those of their descendants" (B. Cuartero, II p. 565). It is quite possible, therefore, that two years later, during his double journey through Italy, on the way to and from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, he was looking for models for sepulchral monuments, although the laconic nature of his travel diary prevents us from affirming this. Although in this diary he only seems to be moved by the florid marble work on the façade of the Carthusian monastery in Pavia, he must have seen in Rome, where he stayed for three months, the triumphal arch tomb of Pope Paul II which would have served as a model for that of Fancelli and the diffusion that this type of parietal tomb already had in Italy, a typology that in Spain, until then, had only been used by two prelates and close relatives of his, his mother's uncle and cousin respectively: the Great Cardinal Mendoza and Archbishop Hurtado de Mendoza (M.J. Cantera, 1987, 115).

Be that as it may, the Marquis of Tarifa must have had a very precise idea of the type of tomb and iconographic discourse he wanted for his parents when he stopped for a few weeks in Genoa before continuing his journey to Seville. None of the work done in Genoa or the earlier work of the two sculptors he selected, Pace Gaggini and Antonio Maria Aprile, are related to the tombs they carved for the Marquis of Tarifa. suggests that the programme was drawn up by the Marquis of Tarifa himself.either verbally or, more likely, by handing him some tracings. In fact, eight years later, when he commissioned Antonio Maria d'Aprile and his partners - Pace Gaggini had already died - to do the much less important tombs of his ancestors, the notary in the contract signed attests to having received "a memoir and three drawings", a clear indication that the marble workers must have received similar documents for the much more complex paternal monuments.