History of the House of Pilate

From Mudejar to Romanticism

This palace is the result of a long process of construction and addition of new houses and plots of land Three main construction phases can still be easily distinguished today: a primitive medieval palace built at the end of the 15th century, a Renaissance extension and reform carried out in the twenties and thirties of the 16th century and, finally, a new palace built around 1570 adjacent to the old one and embracing its orchard. On top of this palace, which would not grow any more, the following buildings would continue to be built reforms to the 20th century. You can access each of these stages by clicking on the dates on the chronological axis which mark the conclusion of each of them.

The origins: The Mudejar palace (1483-1505)

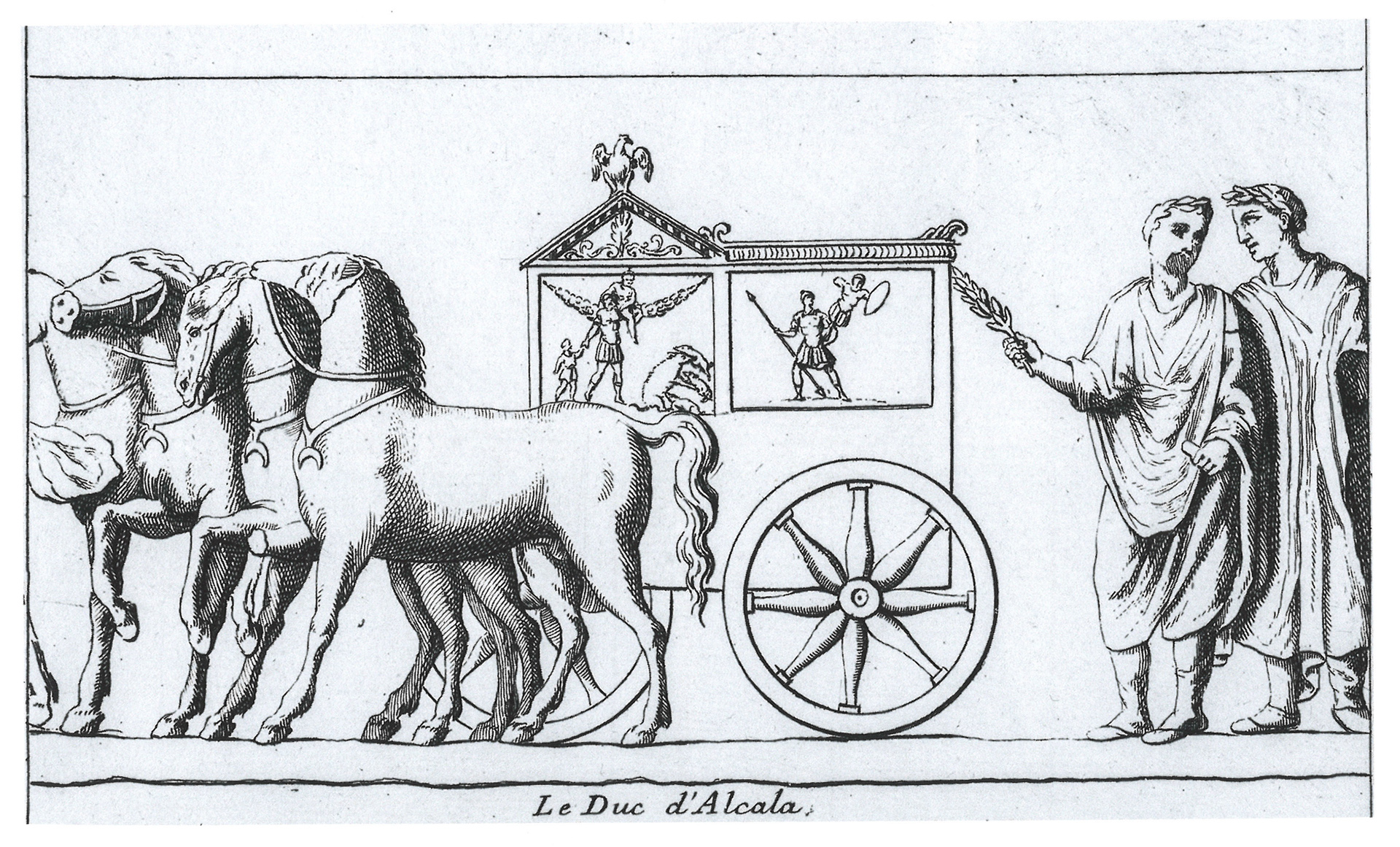

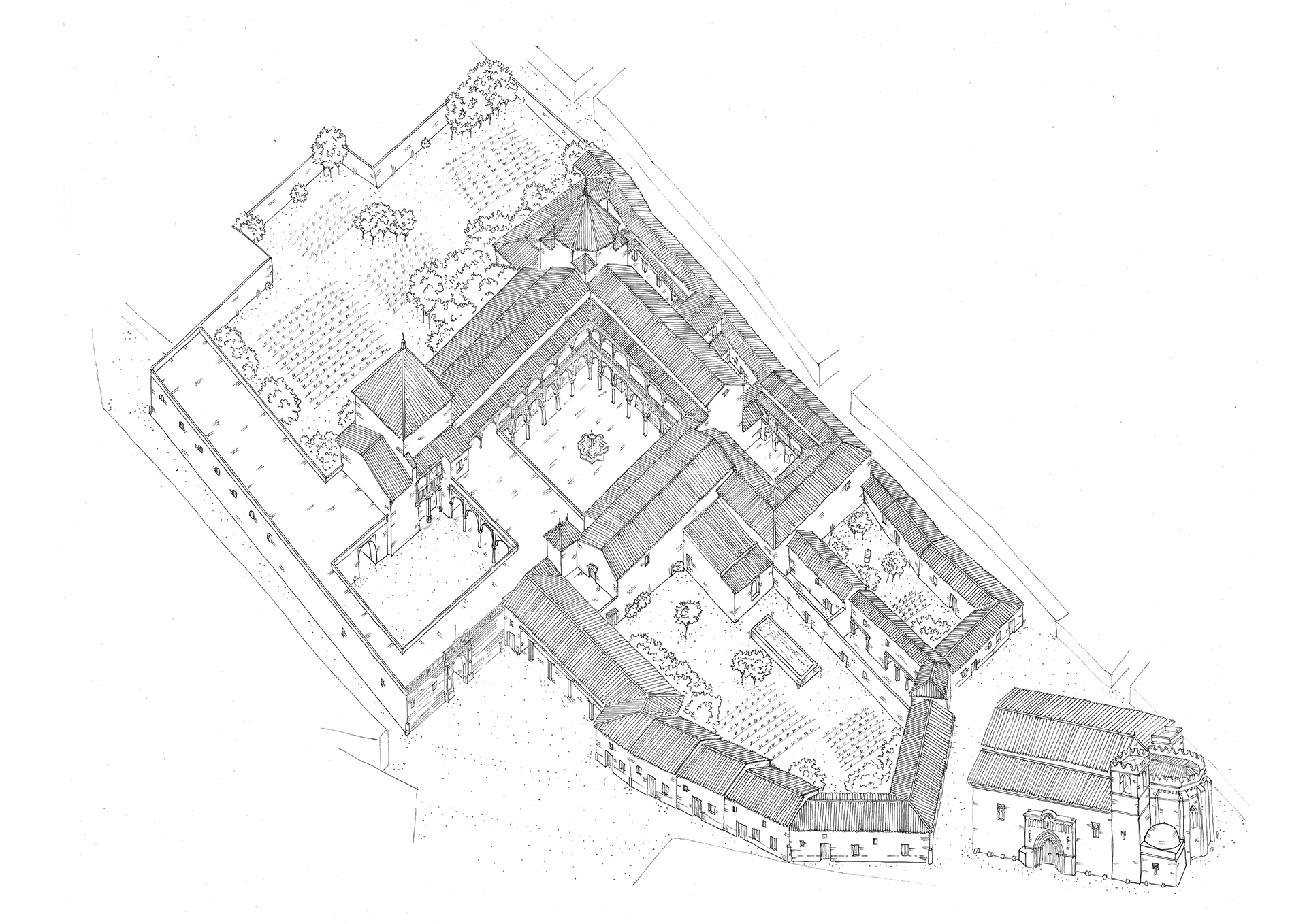

Dibujo que propone una reconstrucción hipotética del palacio primigenio de los Adelantados Mayores, en el que cabría destacar: la recién creada plaza de Pilatos, en la que se levantó, como nuevo acceso al palacio, la actual fachada de ladrillo agramilado con una portada distinta a la genovesa actual; un apeadero más sobrio, carente del actual intercolumnio, espacio ocupado por uno de los salones que abrían al patio y que estaba flanqueado por dos torrecillas; un patio principal porticado en tres de sus lados formando una U que comunicaba con otro pequeño patio, presumiblemente preexistentente, y que sostenía una planta alta que forma una L con el torreón en su centro.

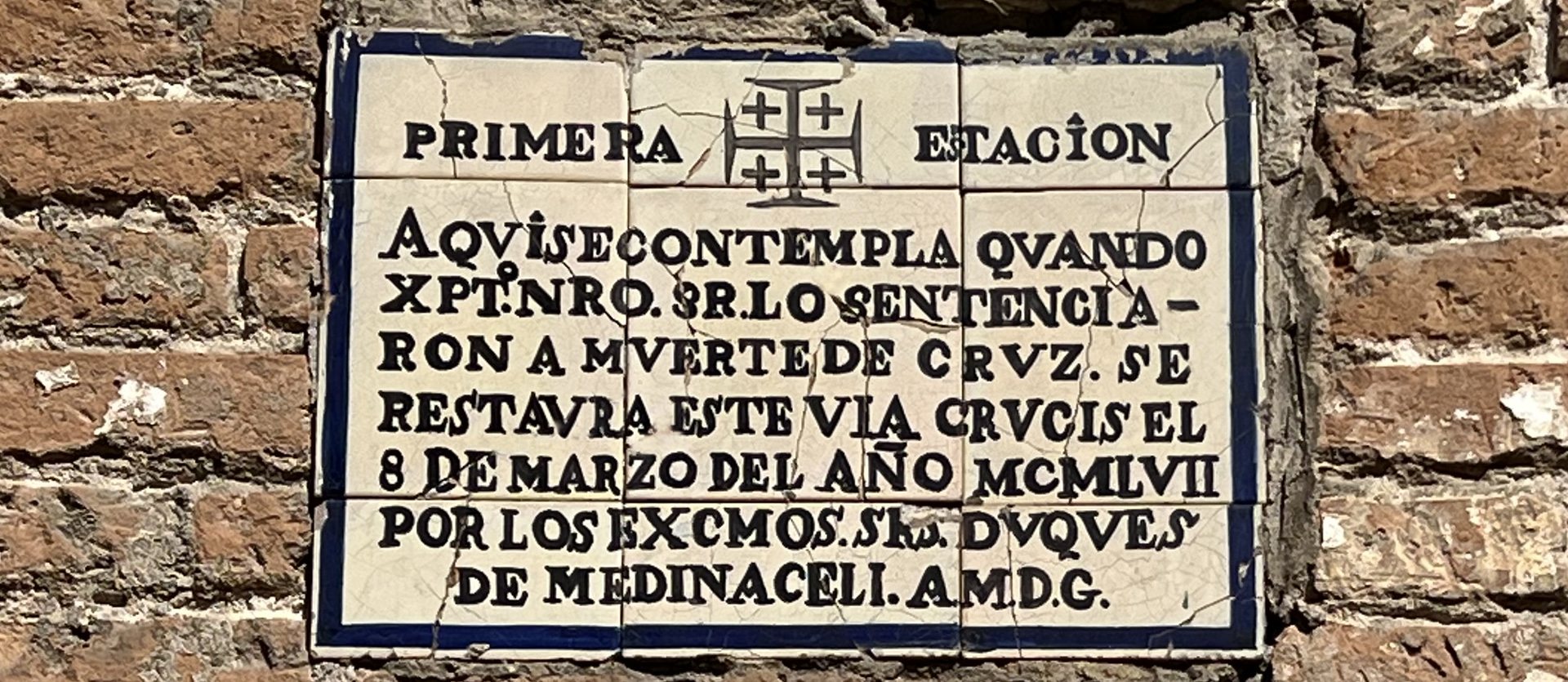

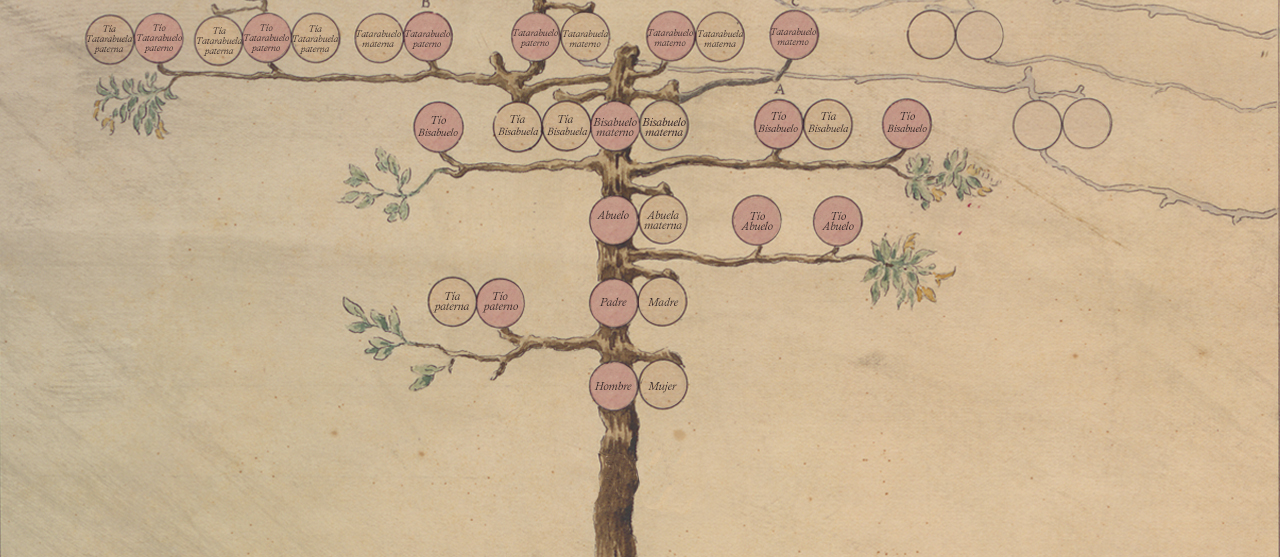

The medieval palace was built by the Adelantados Mayores de AndalucíaPedro Enríquez and Catalina de Ribera, on a group of houses that they had acquired from the Royal Treasury in 1483The description in the contract of sale does not allow us to identify this group of houses within the current perimeter, as the boundary indicates, "...". The description given in the contract of sale does not allow this group of houses to be identified within the current perimeter, as the boundary indicated, "...", is not the same as the one indicated in the contract of sale.the royal street"The name of the street was the name given to any public street, but it does point to a singularly valuable particularity: that of having a direct connection to the water of the Carmona watercoursesThis was a monopoly of the Crown which, as a gracious concession, very few estates in the city had and which allowed them to have a landscaped garden.

This original nucleus was enlarged by the Adelantados with the acquisition of new houses, not only with the aim of increasing the living area, but also with the aim of demolishing some of them to create a private square, the current Plaza de Pilatos, on which to erect the new façade of their palace with a brick wall (V. Lleó, 2017, pp. 24 ff.).

The medieval palace was built around a courtyard who then had U-shape and which can be identified by the smooth conical capitals crowning the columns on three sides. The works extend between 1483 and, at most 1505the year of Catalina de Ribera's death, although it may well have already been completed in 1496when Catalina acquired the house of the Pinedas for her second son, now the palace of Las Dueñas, whose renovation was modelled on this one.. Above these galleries, an upper floor was built on two sides of the courtyard, leaving the southern bay free. The architecture and coffered ceilings of all the rooms that open onto these courtyard galleries, both on the ground floor and on the upper floor, date from this period, which gives us an idea of a scale and luxury unheard of at the time which astonished contemporary travellers and are still only comparable today with the royal palace of the Alcazar.

Arch with the truncated cone-shaped capitals characteristic of the galleries in the courtyard of the medieval palace, which formed a U-shape to which the perimeter halls opened.

The original palace can also be distinguished by the heraldry present on the many alfarjes that still survive and which, on the ground floor, contrasts with that which appears on the tiled walls covered by the 1st Marquis of Tarifa in the 1530s. On the doors of the chapel are painted at a height and scale that make them easy to read. arms of Enriquez y Sotomayor, This motif is repeated in the joints of its ribs and in the aliceres of the alfarjes of the upper and ground floor halls, except in those where they have been modified at the same time, as in the Judges' Rest Hall, or removed in the 17th century, those of the corridor of the Pacheco hall. The use of the arms of Sotomayor instead of those of Ribera is due to the fact that, until 1509, The latter corresponded to the first-born son of the House of Ribera, the aforementioned Francisco, son of Don Pedro's first marriage, so the new marriage combined those of the Enriquez family with those of the maternal lineage of the House of Ribera, those of its founder's mother, Inés de SotomayorThese are the arms that the 1st Marquis of Tarifa ordered to be placed on the tombs he ordered for his parents.

Arms of Enríquez and Sotomayor on the sill of one of the coffered alfarjes on the ground floor. These arms, which are those used by Pedro Enriquez and Catalina de Ribera, are one of the elements that allow us to identify with greater certainty the rooms of the house dating from the 15th century.

A part of this 15th century palace, the one that bordered Imperial Street, was demolished at the beginning of the 20th century as part of the works to align the street, demolitions that were extended to enlarge what is now known as the Jardín Chico (Small Garden) to a small courtyard that connected with the main courtyard and which appears partially drawn in late 19th century plans. The heraldry still makes it possible to distinguish the primitive structure of their representation spacesThe buildings were built around the courtyard, in which stood a palace in each of its pandasThe expression that at the time designated a rectangular room with chambers attached to its short sides, a syntagma that rises entirely in the north bay, has disappeared in the south, due to the intercolumniation built by the Marquis of Tarifa, and remains only partially in the east, due to the staircase that he himself built in the 1530s.

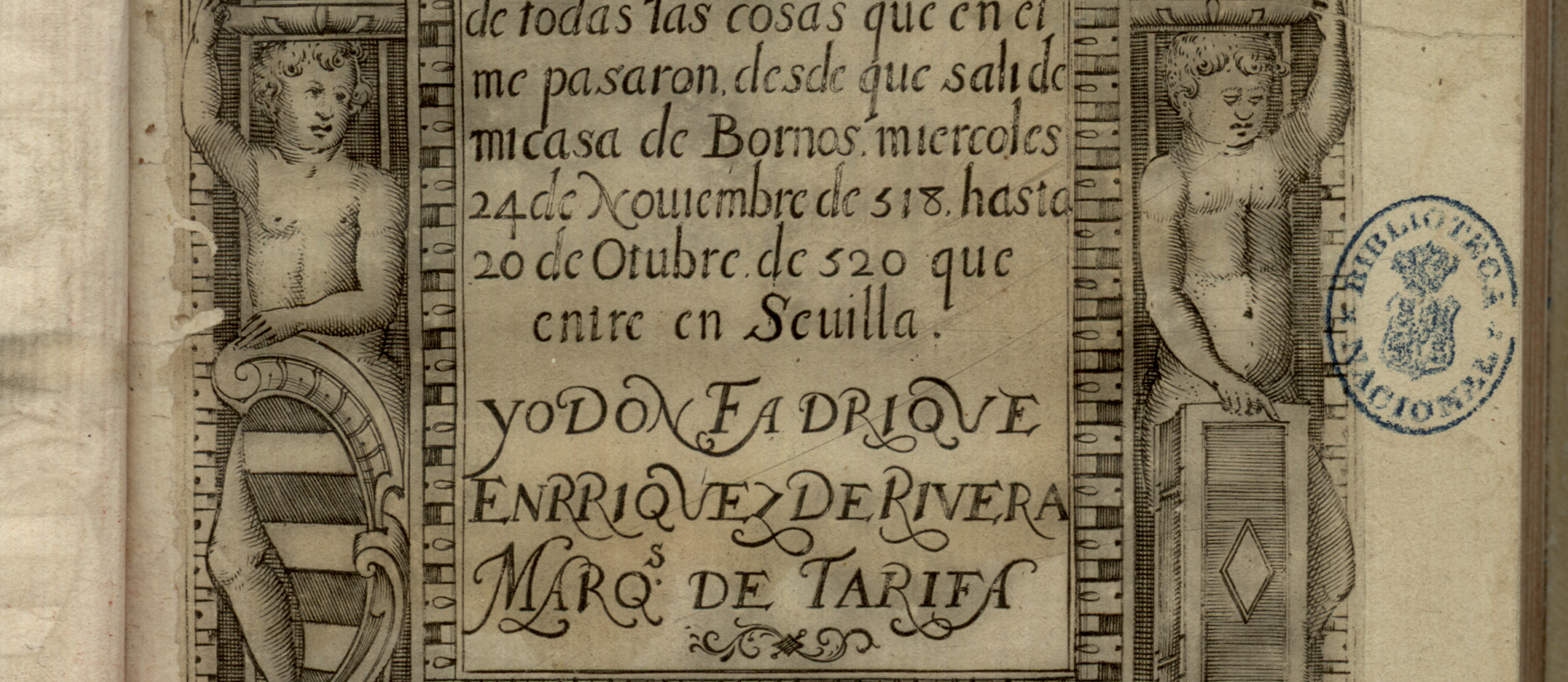

The palace of the Marquis of Tarifa (1525-1539)

Dibujo que propone una reconstrucción hipotética del palacio con las reformas y adiciones realizadas por el marqués de Tarifa entre su regreso a Sevilla en 1520 y su muerte en 1539. Las más visibles son: las adquisiciones de nuevos solares que alcanzan a ocupar toda la manzana existente entre la iglesia de San Esteban y el convento de San Leandro; el cierre de la panda Este del patio; la edificación de una torre para alojar la escalera; la conversión del salón de la panda del patio adyacente con el apeadero en doble intercolumnio y la edificación de un nuevo «guardarropa» o «cámara de maravillas» en uno de los solares que le permitieron ampliar la huerta, hoy «Jardín Grande».