History of the pazo of Oca

From "hortus conclusus" to the landscape garden

The pazo of Oca and its gardens are the result of the transformation of a primitive medieval fortress with a small preserve into a palace with an orchard and pleasure gardens, a mutation modelled in the 18th century on the Baroque court palace and, in the 19th century, on the romantic and landscape innovations of the gardens of royal palaces. This history is divided into periods, which you can access by clicking on each date on the chronological axis below, indicating their beginning.

The first lords of Oca

Although tradition claims that an ancient fortress existed here as far back as the 12th century, the earliest surviving material remains date from the mid-15th century and are contemporary with the first documented lords of Oca: Álvaro de Oca and his son Suero. The latter took part on the side of the Count of Camiña, Pedro Álvarez de Sotomayor (better known by his nickname, Pedro Madruga) in the battles that, on the occasion of the succession to the Crown of CastileDuring the last quarter of the 15th century, they confronted a large part of the Galician nobility, supporters of the daughter of Henry IV (Juana "la Beltraneja") against the powerful archbishop of Santiago, Don Alonso de Fonseca, who supported the cause of Princess Isabella, the future Isabella the Catholic. The prelate, aided by the troops of the Count of Monterrey, punished the lord of Oca by seizing the place and its fortress in 1477. The Fonseca's victory meant that this lordship was consolidated within the jurisdiction of the mitre of Compostela until 1564, when it became part of the Crown's patrimony.

Related content

A Renaissance "hortus conclusus".

Philip II, by deed of sale signed at El Pardo on 15 November 1586, sold for 195,775 ms. the small estate of San Esteban de Oca, with its civil jurisdiction, to a lady named Maria de Neyradaughter of a councillor of Santiago de Compostela, Juan de Otero y Neira, and widow of another, don Gonzalo de Luaces. This lady, in 1590, added it, through her will, to the entailed estate she had received from her father and her late husband, constituting a bond that in addition to this state included, among others, the offices of perpetual alderman of the city of Santiago, the ".large houses"and the patronage over some chapels in Santiago de Compostela (A.S. Iglesias Blanco, 2008, p. 110 ff.). He was succeeded by his son, Juan de Neiramarried to María de Mendoza y Bermúdez de Castro who, in turn, was succeeded by his daughter Catalina, who was married to Juan Gayoso NoguerolThe surname "Gayoso", which, from then until the 20th century, will point to all the successors in the aforementioned entailed estate and, therefore, to the lords and owners of Oca.

The primitive fortress of Oca, the one lost by Suero, may well have consisted of two towers joined by an intermediate body, all crenellated. In the last third of the 16th century, in the time of the Neira family, some transformations were made of which there is still clear evidence. Thus, the doors facing each other in the entrance hall, crowned with the arms of the Neira and Luaces families, although this was not their original location, indicate their intervention in the primitive fortress, long before the 18th-century reforms. On some of the gates of the wall surrounding the perimeter of the gardens, the arms of the Neira, Luaces, Bermúdez de Castro and Mendoza families can still be seen today, those of the marriage of the aforementioned second lords of Oca, which evokes an ancient orchard formed by terraces that would have been pursued, with its walling, the ideal of the hortus conclusus that the Renaissance inherited from the Middle Ages and in which the construction of the intramural water channelling system which would flow into a dam, mentioned in the will of María de Neira in 1594, which would have been located in what is now the pond above.

The palace transformation

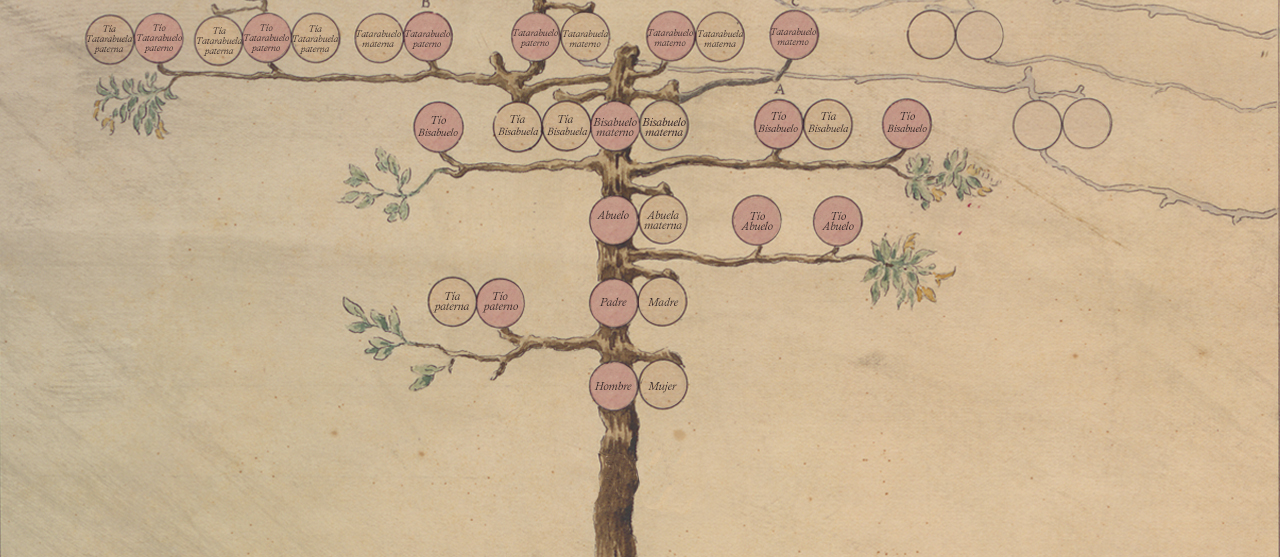

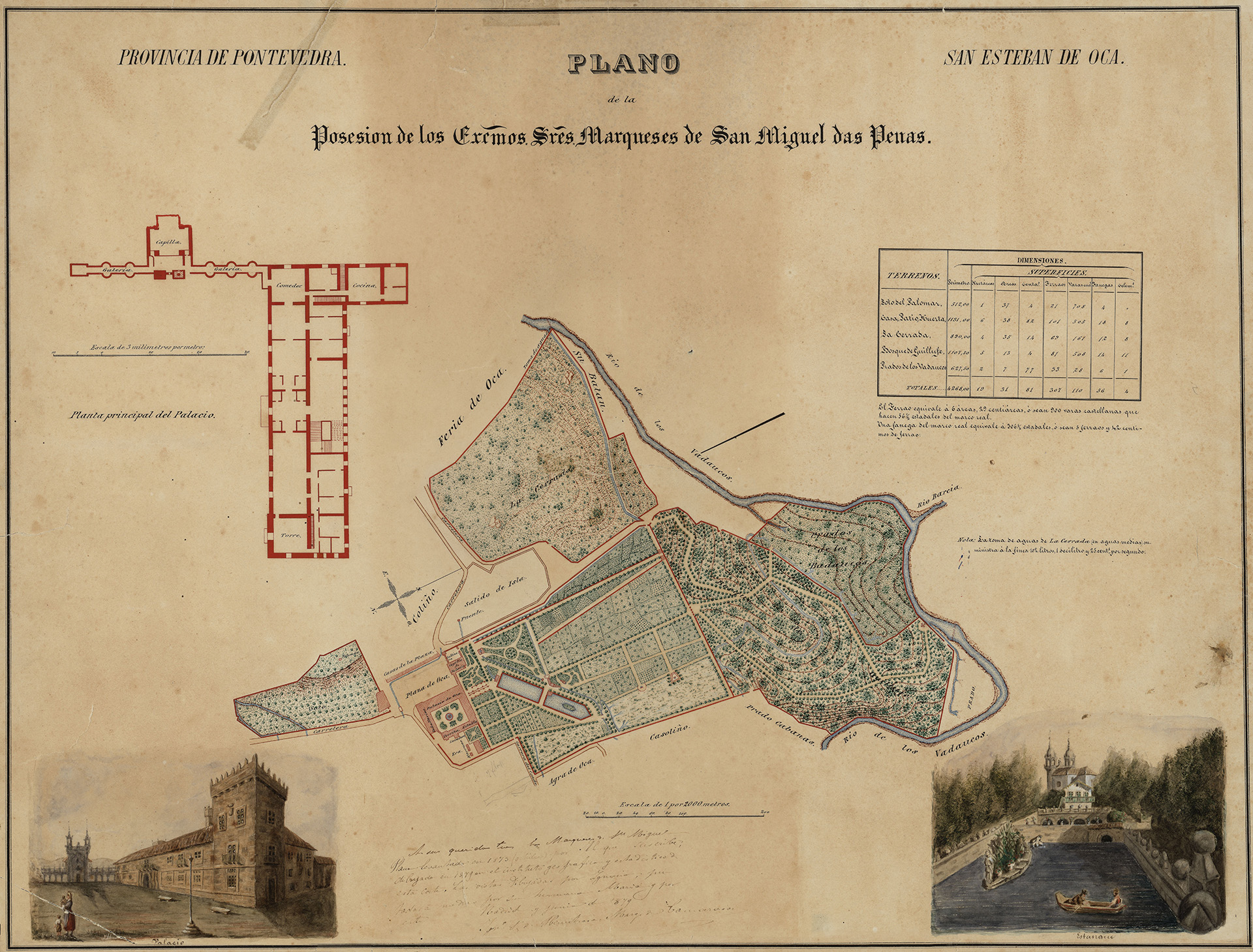

Although this plan dates from 1805, it shows the main façade of the palace of Oca and the interior layout of its noble floor plan, with an indication of its uses, as they were in the mid-18th century, with the palatial transformation of the old medieval fortress.

Three generations succeeded Doña María in the lordship of Oca until, at the beginning of the 18th century, it was the turn of Andrés Gayoso Neira whose marriage to Constanza Arias OzoresThe death without succession of her two brothers of the House of Amarante - which included two titles of nobility, the County of Amarante and the more recent Marquisate of San Miguel de Penas y de la Mota - marks the beginning, on the one hand, of the palatial conversion of the old fortress of Oca and, on the other, of the successive matrimonial connections that would integrate the lordship of Oca into noble houses of increasing importance until it became part of the high nobility.

The Countess Marquise, like her mother, was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Isabella of Farnese. It was she who provided the marriage with the money and the courtly ways of life that would give a new appearance to the manor house, work on which began in the 1720s.

In the gardens, the most important work of these VI Lords of Oca was the design and construction of the ponds, "worthy - according to Otero Pedrayo - of a cardinal's villa", a description of which can be found in the section "Apuntes visuales" (Visual notes). The landscape architect Consuelo Martínez Correcher, from the study of the papers on Oca kept in the Ducal Archives of Medinaceli, deduced that this 18th-century garden, whose transformation began in its second decade, "was a very beautiful, delicate and palatial orchard with a dual purpose of utility and beautya true eighteenth-century ideal. Its ornate orchard dimension was provided by the outlines of medicinal plants that outlined the food plantations".

The current layout of the interior of the Oca palace is coeval with the transformation of its gardens. Andrés Gayoso rebuilt the old medieval tower and remodelled the bay of the façade overlooking the square and, as a sign of his intervention, carved the arms of his House on one of the faces of the tower. As we are unable to discern with certainty how far the work of the 3rd Marquises of San Miguel das Penas went and where that of his son began, we attribute to the father the noble residence, built on the main façade, and to the son the service area, which occupies the southern bay that separates the courtyard from the palace garden, as it was he who had a hand with the index finger pointing south and the inscription "Prosiga 1746" (Carry on 1746) carved on each side of the last of the "waiting" ashlars in this bay to encourage his descendants to continue the construction that would enclose the courtyard with bodies of the same height. This inscription marks, then as today, the limits of the upper floor of the palace and, as Emilia Pardo Bazán somewhat hyperbolically remarked, from "The prosigase that at one end of the vast building he wrote an unsettling, today almost a second Escorial would have been fulfilled".

The façade bay opened onto the residence of the Marquises of San Miguel and Counts of AmaranteIn the 18th century, this space was known as a large flat, i.e. a group of interconnecting rooms. The eighteenth-century residential space on the main floor complied with the ideal layout that European architects defined for a large flat and consisted of:

- dining room of Their Excellencies, known today as "The Library" for its bookshops, from the 1920s;

- antechamber, camera and cabinet which had a very small size because they were "secret-like rooms where the owner of the house retires to write or study".This space is now used as a bedroom and was accessed both from the dining room and from the "corredor de palo", which was converted into a solana in the 19th century;

- The State Room, now known as Coat of Arms Hall by the beautiful polychrome coat of arms of the Marquises of San Miguel das Penas and Puebla de Parga and Counts of Amarante carved on the ceiling. This room, an essentially feminine space, complied with the eighteenth-century architectural norm of contiguity to the dining room. On either side of the room, symmetrically, are an oratory and an alcove. The fact that some 18th-century architectural treatises found it unseemly that the oratories were placed next to the dais indicates that this must have been common practice;

- Hall of the Continents: so called because of the four alcoves into which it is divided by richly polychrome wooden partitions, dedicated to the four continents into which eighteenth-century geography divided the world. This hall, which is in the centre of the front bay above the doorway, remains exactly as it was in the 18th century;

This room, known as the "Continents" room, because of the four alcoves in its corners dedicated to the four continents known in the 18th century, occupies the centre of the flat built by the 3rd Marquises of San Miguel das Penas in the front bay of the palace.

- Portrait room, renamed as ballroom. It is what the eighteenth-century architect Benito Bails called ".assembly hall"It was used for audiences, listening to music, playing board games, etc. The name of the original portrait room indicates that it was furnished with the portraits that are now in the Gallery;

- Tower Halltoday called "Prince's Room"It was the bedroom of the late Prince of Asturias, the first-born son of King Alfonso XIII, Don Alfonso, whose house was headed by the Marquis of Camarasa. Embedded in the wall is a staircase that led to the third floor of the tower where Until the 18th century, the Archive had beenThis is the function for which high rooms used to be designated, as they kept the papers away from humidity and were easier to protect.

The entrance hall divided the ground floor into two spaces: on the right the games room o "lower hall where the trick table used to be"The name of the billiard table in the 18th century. which still retains its playful function and on the left two rooms with agricultural useone called "Panera", today known as "Panera", today known as "Panera".the tulle room"(granary in Galician) and in the background the lower room of the tower, known as the "Vodega".

Façade of the chapel of San Antonio de Padua, built between 1731 and 1751, presiding over the pazo's original working square.

The social promotion of the Lords of Oca continued with their son, Fernando Gayoso Arias, 4th Marquis of San Miguel de Penas, who married the heiress of the Marquisate of Puebla de Parga, Maria Josefa de los Cobos Bolaño and gave new impetus to the Pazo by continuing the work on the palace and completing the construction of its chapel in 1751, which became the backbone of the gardens and orchards, as well as the current access square to the pazo, which at that time was its labour square, a space that with the fortress-palace on one side, the group of popular houses on the other, all under the presidency of the church, reflects the social relations that existed in the 18th century.

The chapel was built between 1731 and 1752.The chapel was designed by the Dominican architect Fray Manuel de los Mártires, one of the representatives of the late Galician Baroque, author, among others, of the monumental façade of the monastery of San Martín Pinario in Santiago. This chapel replaced a primitive oratory which, at the end of the 16th century, María de Neira dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua, an invocation that the new chapel maintains, a description of which can be found in the "visual notes" section.

As we have said, it was Fernando Gayoso who completed the service wing that occupied the southern bay, which today separates the palace garden from the courtyard. Parallel to this façade was a formal vegetable garden, at the same time ornamental and useful, laid out in grids with a granary located approximately opposite the chapel, an orchard for which the steward, who lived above it, was directly responsible and which began to be replaced by the current ornamental garden, which we call the palace garden, in the 19th century.

This service area consisted of: a pantrya dining room; a kitchen that, in addition to the "lareira", the It retains all its original features, although it has lost its function when it was converted into a living room; the butler's roompreserved as it was in the 18th century, and finally, the family dining roomThe family, i.e. domestic service (meaning of "family" in the 18th century).

All the floor slabs of the palace are made of wood except those of the huge kitchen, which is located on the upper floor and supported by a stone vault which gives access from the courtyard to the current palace garden, in order to support the enormous weight of its "lareira" and to avoid the danger of fire from the wood burning in it almost permanently.

Integration into the high nobility and completion of the eighteenth-century garden

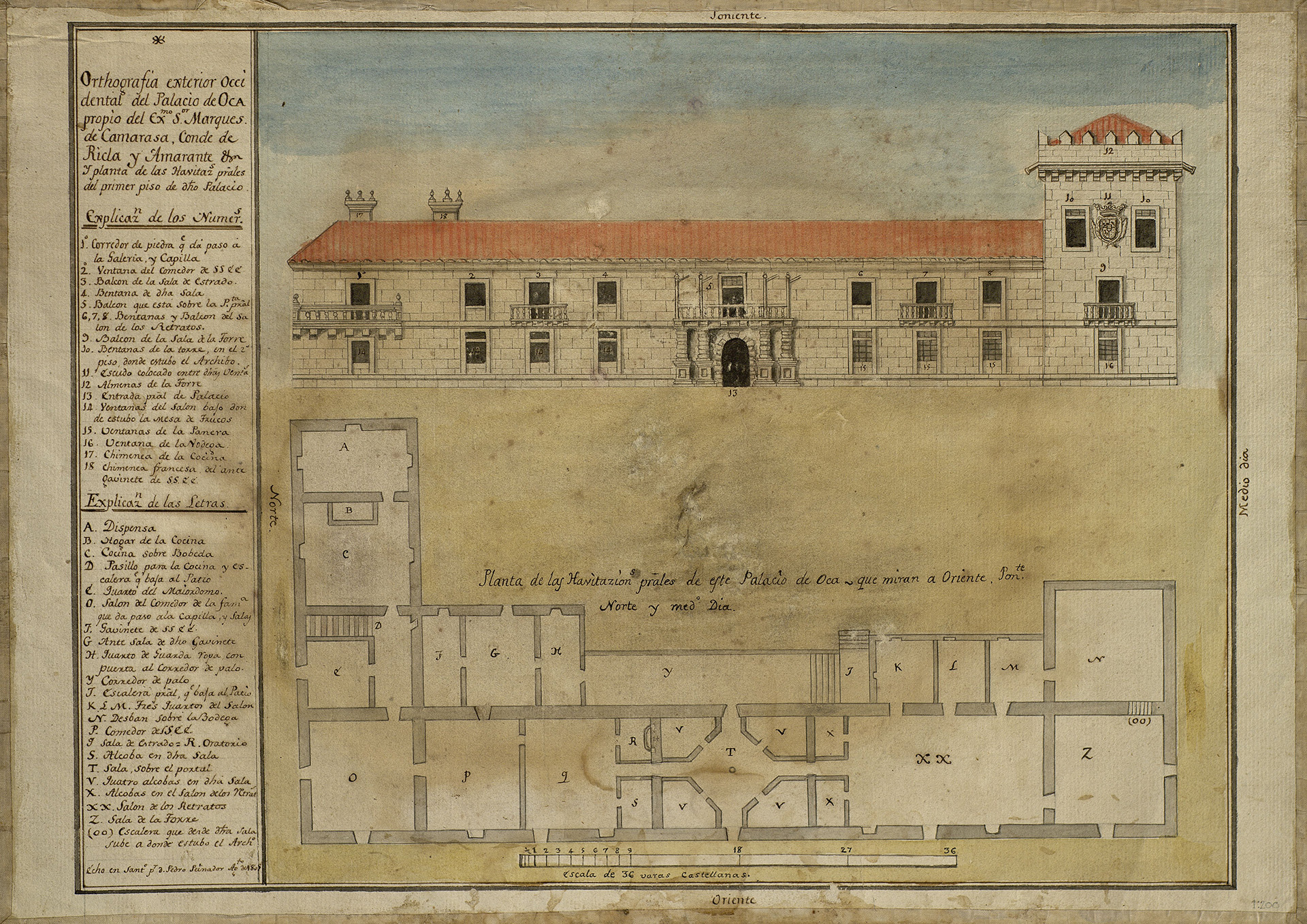

This plan, commissioned in 1805 by the last Lord of Oca, shows the complete transformation of the garden in the 18th century, in which, on an oblique axis, the splendid ponds surrounded by a grove of trees stand out, a space which, together with the formal grid of its design, built with borders and the waterworks that run through it, show that its model was the court garden of the Baroque period.

On the death without succession of the first-born son of this marriage, Francisco, he was succeeded by his brother Domingo Gayoso de los Cobos who, through an unusual series of deaths, added to all the titles and territories of his parents, in addition to the very important lordships, outside the Galician world and scattered throughout different regions of Spain, the titles of conde de Ribadaviaby succession of his second uncle Diego Sarmiento de Mendoza, and, on the death without succession of his second aunt Baltasara Gómez de los Cobos, the whole household Marquis of Camarasawith the condados de Ricla y of Castrogeriz and the estates that the secretary of Charles V, Francisco de los Cobos, had acquired in the Kingdom of Jaén, which included his pantheon in Ubetense: the Sacra Chapel of El Salvador in Úbeda. Domingo Gayoso de los Cobos thus became one of the leading figures of the Spanish nobility at the end of the 18th century and, although his intervention in Oca is not very important, his contribution to Galicia's architectural heritage is, however, significant, as, among other works, he built the magnificent façade of his residence, the old palace of the Counts of Amarante in Santiago de Compostela, today the seat of the Palace of Justice. His son, Joaquín Gayoso de los Cobos y Bermúdez de Castro, who lived through the abolition of the jurisdictional lordships, was the last Lord of Oca and its first owner.

As for the works in the second half of the 18th century, they were of lesser scope. Francisco Gayoso and his successor, his brother Domingo, ordered the building of the washhouse of the Carrera del Conde and the Trout FountainThe old dam was enlarged, some new properties were added and the walled enclosure of the garden was completed.

Lavadero de la Carrera del Conde, one of the stone elements that, together with the trout fountain, was added at the end of the 18th century.

The result of all these eighteenth-century transformations has been reflected in a map entitled "Southern exterior spelling of the Palace and Chapel of Oca".known as the Peinador Plan, commissioned in 1805 by the last lord of Oca, Joaquín Gayoso de los Cobos, 12th Marquis of Camarasa. This plan, which should be read with caution, as it does not seek to reflect reality to scale, but rather to represent it schematically, shows us a very formalistic grid gardenThe garden, with numerous architectural elements and perfectly aligned plantings, in which it is very difficult to distinguish the part dedicated to the ornamental garden from the part destined for fruit and vegetable production. The lack of proportions in Peinador's plan and its peculiar orientation make it difficult to compare with more modern plans, but a careful reading allows us to identify in the present garden, despite the numerous alterations introduced later, the reticular framework of the eighteenth-century garden.

Related content

The Chapel of the Saviour

Vié's landscape reforms

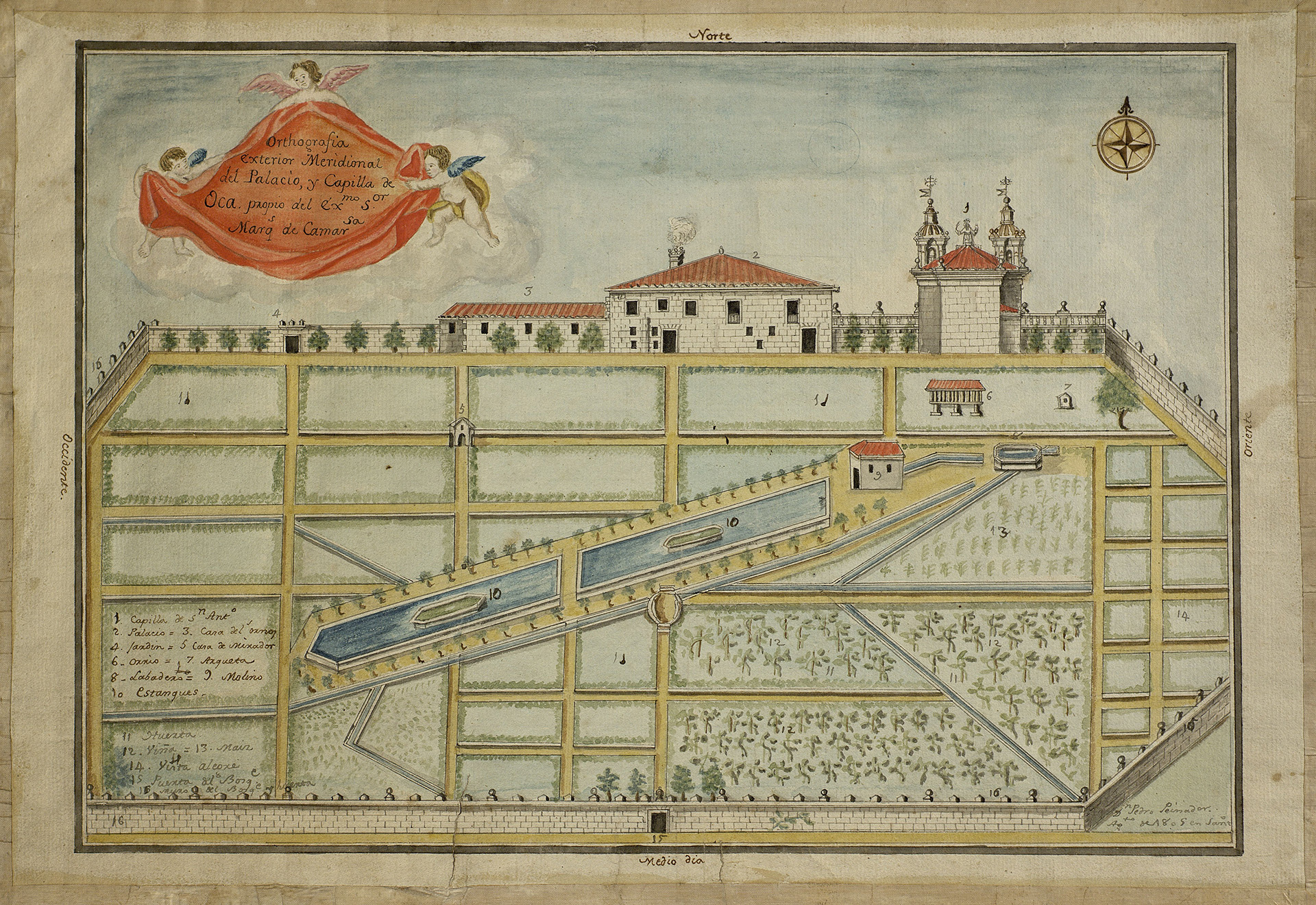

Plan from 1879 showing the romantic and landscaping reforms introduced by the 6th Marquises of San Miguel das Penas with the help of the French gardener, François Viet. It is perfectly visible the grove created on one side of the upper pond, from which the stone boat has been removed and, above all, the emphasis placed on a new axis of the garden: the current Paseo de los Tilos which connects with the Guillufe wood, where the paths are marked out with rows of oak trees.

From the marriage of the XII Marquis of Camarasa, Joaquín Gayoso de los Cobos y Bermúdez de Castro, with Josefa Manuela Téllez GirónThe firstborn, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, had six children, among whom the inheritance had to be divided in accordance with the new laws of the Liberal State. The main titles and properties went to the first-born son Francisco Gayoso de los Cobos y Téllez Girón who, when he died in 1860 without succession, left all his property to his brother Jacobo, the youngest of the family. However, the pazo of Oca went to one of the younger daughters, María Encarnación Gayoso de los Cobos to whom, in 1857, his brother François ceded the marquessal title of San Miguel de Penas y de la Mota. Jacobo Gayoso married Ana de Sevilla y Villanueva and from their marriage three girls were born, who were soon orphaned and spent long periods in Oca, under the care of their aunt María Encarnación. The first-born of the three, Francisca de Borja Gayoso de los CobosIn 1871, she inherited the bulk of the Camarasa house from her father and, in 1879, she also received the property of the Oca palace from her aunt, who died without inheritance. Francisca married Ignacio Fernández de Henestrosa y Ortiz de MioñoCount of Moriana del Río and Marquis of Cilleruelo.

The only major modification this 18th century palace underwent in the 19th century was the construction of the the solana on stone arches which presides over the main façade of the courtyard and replaces a primitive 18th century wooden corridor. It was built in the 1960s, at the same time as the landscaping reforms introduced in the gardens by François Viet Bayez, as we shall see. Its authors were the Marquises of San Miguel de Penas, Mª Encarnación Gayoso de los Cobos - who, in application of the reforms of the Liberal State, inherited the pazo of Oca as owner and received the title by distribution and not by succession - and her husband, Manuel Fernández de Henestrosa y Santisteban. The widening of the bay that this modification entailed made it possible to introduce corridors, an element typical of 19th-century residential uses, but foreign to those of the 18th century, in which communication was established through the halls.

In the second half of the 19th century, these same Marquises of San Miguel das Penas commissioned the gardener of the Royal Palace and executor of the Jardín del Moro in Madrid, François Viet y Bayez - who signed his works with his surname Vié in Castilian -, a renovation of the gardens. Once again, a plan, this time entitled ".Possession of the Marquises of San Miguel das Penas".The work commissioned by Ignacio Fernández de Henestrosa y Mioño in 1879, with the assistance of the Geographical and Statistical Institute, clearly shows the result of this intervention, which focused mainly on the design of landscaped layouts for the garden areas closest to the palace and, quite possibly, also on the opening of the gardens to the forest of GuillufeThe garden, with a plantation of lime trees that, like a promenade, accentuated a pre-existing axis that led to a clearing in the forest from which various paths started out in all directions.

Their action also affected the courtyard, which was ordered by means of grass and plant bordersThe four paintings in the garden of the house closest to the chapel, whose sober geometry was replaced with winding bordersThe mill of the ponds, which was crowned by a Swiss chalet, a renovation shown in the drawing in the lower right-hand corner of the 1879 plan, of which a project and photographs are also preserved. Mona Fountain and the newly restored garden of Philemon and Baucis and, finally, to the area we know as the grove o Garden of Vié, as it is the only space that remains today as this French landscape designer conceived it, a garden that forms a triangle bordering the aqueduct, the camellias promenade and the dam of the streams.

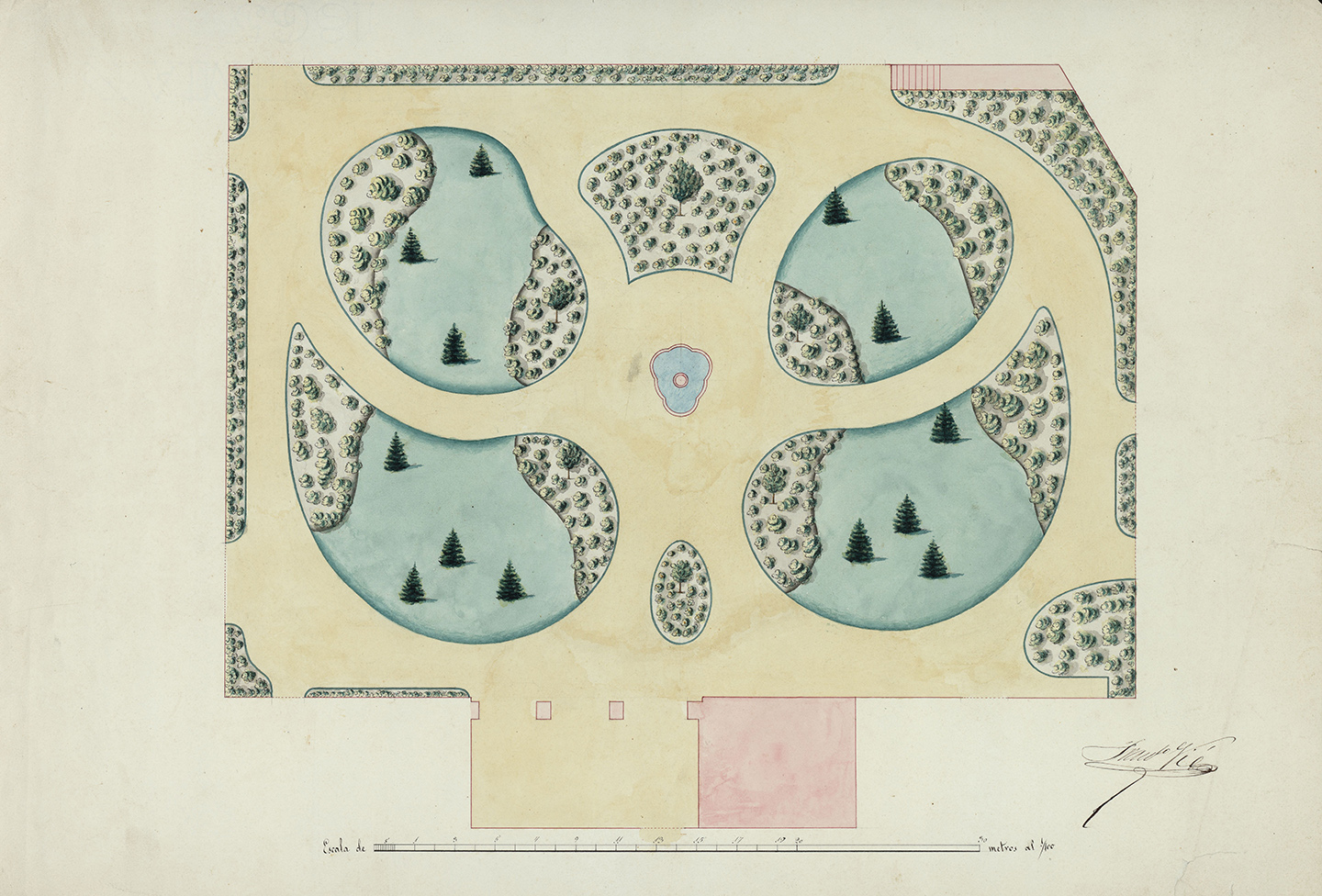

Plan of one of the proposals for the landscaping of the entrance courtyard of the pazo of Oca, which is kept in the Medinaceli Archive, signed by Francisco Vié, gardener of the Royal Palace in Madrid. It is not clear which of them was ever used. In any case, the only thing that remains is the triangular lobed fountain in the centre.