Stations of the Cross to the Cross of the Camp

From Jerusalem to Seville

For the 1st Marquis of Tarifa, the main event of his life, as he himself proclaims, amidst Jerusalem crosses on the façade of his house, "4 days of August 1519 entered Iherusalem"The highlight of this journey was his pilgrimage to the Holy Land between 1518 and 1520, the fifth centenary of which has recently been celebrated, and the highlight of which was the Way of the Cross that he made in the Holy Land between what was pointed out to him as the ruins of the Praetorium and Mount Calvary. Transcendental for him, its consequences were no less important for Seville, since, as Don Fadrique was exposed to the best of contemporary Renaissance architecture on his double journey through Italy, he brought to the city new forms which, in a surprisingly short period of time, would transform its urban planning and, by instituting a Way of the Cross that recalled the one carried out in the Holy Land, would transmute the sensibility with which the city commemorated the Passion of Christ, in what has traditionally been seen as the seed of the Holy Week processions.

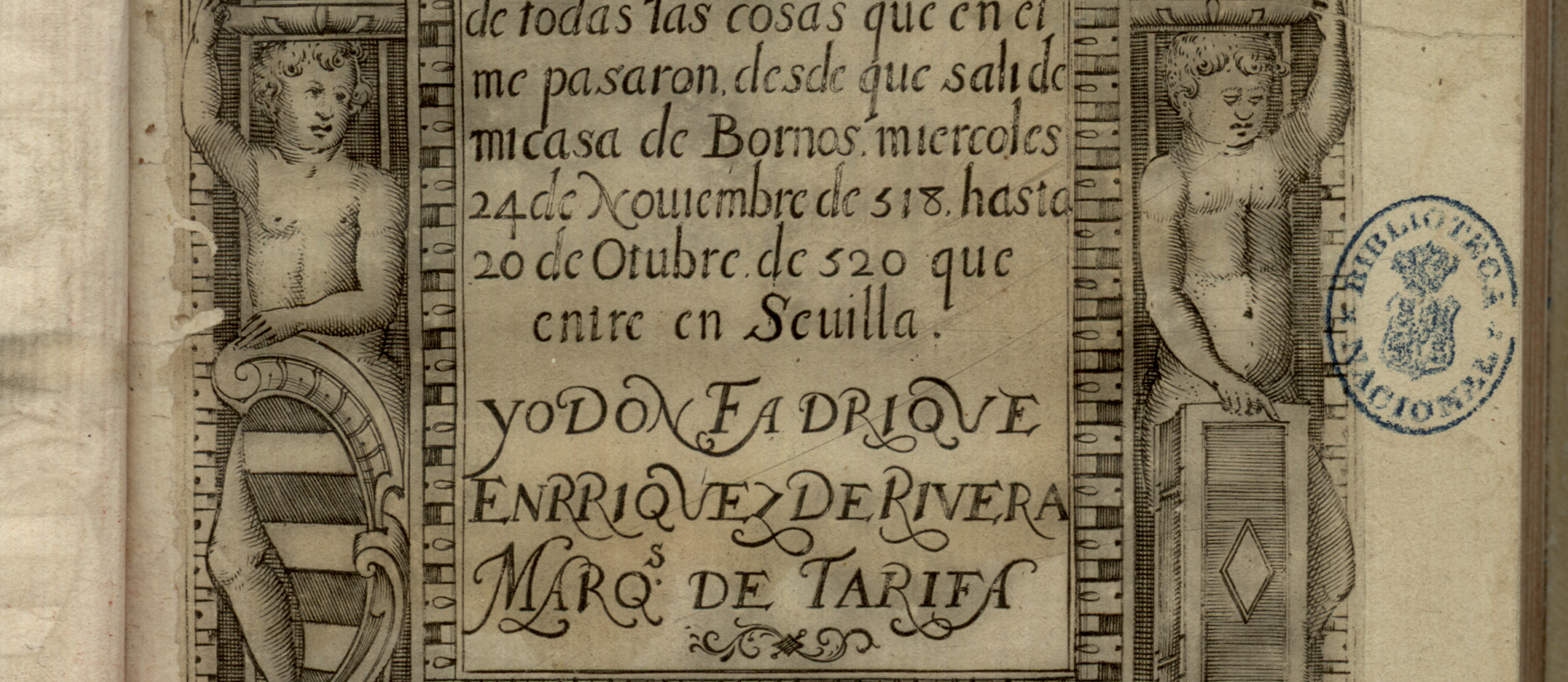

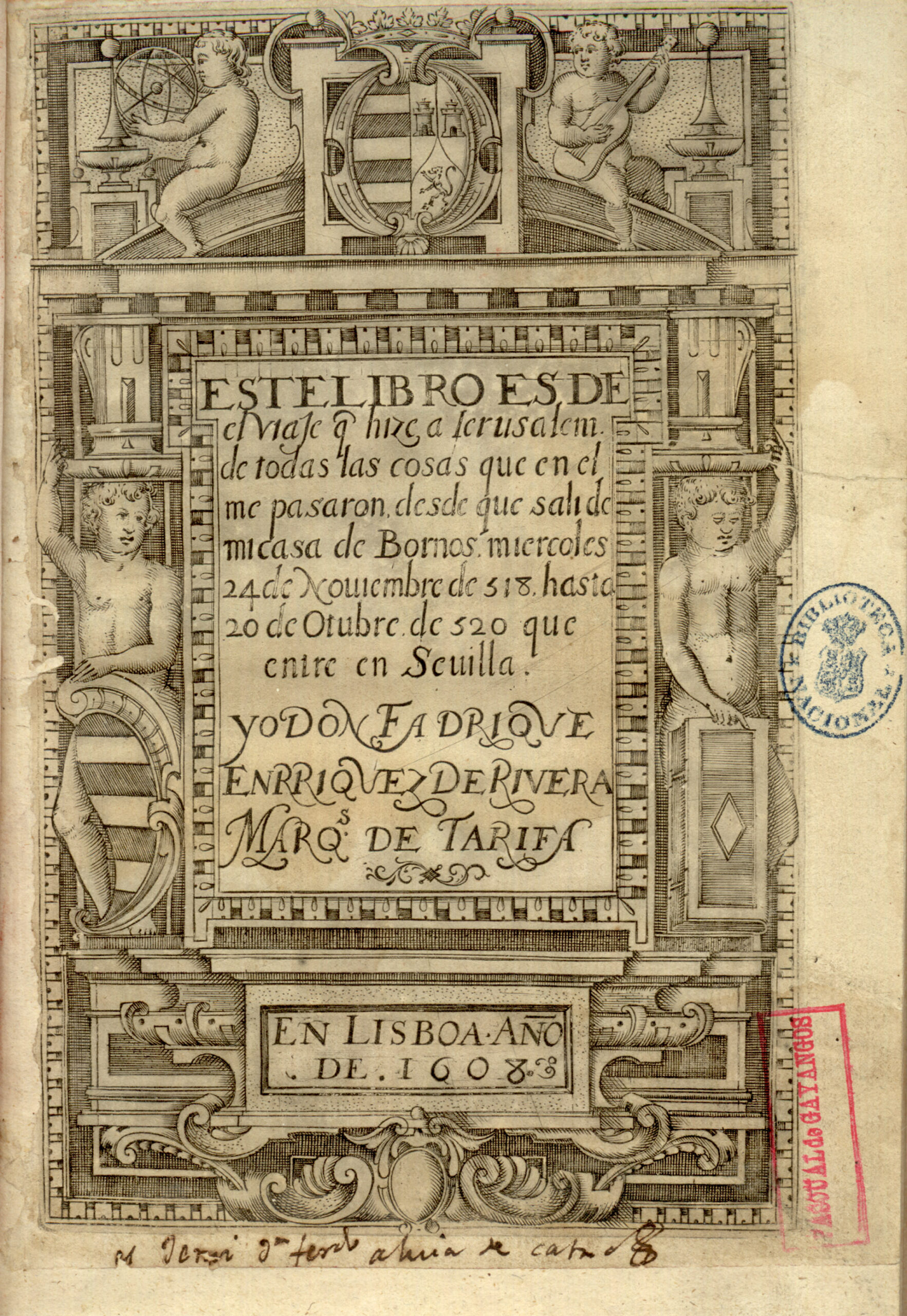

"This book es del viaje que yo don Fadrique enrriquez de rribera, marques de tarifa adelantado mayor del andaluzia hize a Jerusalén de todas las cosas que en el me pasaron desde que sali de mi casa de bornos, que fue miercoles veinte i quatro de nobienbre de quinientos i diez i ocho hasta veynte de otubre de quinientos y veinte que entré en Seuylla."

This is how Fadrique Enríquez de Ribera, 1st Marquis of Tarifa and Adelantado Mayor of Andalusia [1476-1539] begins his account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, which recently marked the 500th anniversary of his return. Perceived as a watershed in his life, Don Fadrique sought to perpetuate the memory of this journey in various media, on paper as mentioned above, but also in stone, with inscriptions alluding to his entry into the Holy City placed in the most visible places in his palaces in Seville and Bornos: on the triumphal arch of his new façade, in the former; fastening the arch spandrels on the perimeter arches of the courtyard, in the latter. He also wished to immortalise the memory in some other medium that has not stood the test of time, as in the gifts he made to the Carthusian monastery in his will: his pilgrim's hat, his staff and the stones he had collected from the ways of the Stations of the Cross he made in Jerusalem.

A relevant event for posterity, as the aforementioned manuscript has repeatedly deserved the privilege of printing, it was no less so for his contemporaries, as proclaimed by the different manuscript versions of this journey that have been preserved, and the existence of a document in the library of the monastery of Guadalupe that includes numerous passages on the Holy Land and declares as sources, on the one hand, a "...", and on the other, a "...".booklet"On the other hand, the oral descriptions of the entourage that accompanied him, testimonies to which the copyist monk had access during the brief stay that the marquis made at the monastery in Cáceres on his return.

Title page of the 1608 Lisbon edition of the diary of the pilgrimage to the Holy Land of the 1st Marquis of Tarifa.

That booklet, now lost, to which the manuscript in the monastery of Guadalupe refers, is the diary in which Don Fadrique minutely noted down news and details of his pilgrimage journey and which forms the basis of all the manuscripts and printed matter that have been preserved, the oldest of which, from which we have transcribed the incipit, is a partial autograph of the famous poet and musician Juan del Encina who accompanied the Marquis from Venice to the Holy Land, This document was bequeathed by Don Fadrique, along with all or part of his library, to the monastery of the Cartuja de las Cuevas, pantheon of the house of Ribera, and if it is preserved today in the National Library it is thanks to the Sevillian polygrapher Pascual de Gayangos who saved it from the painful plundering of Spain's bibliographical heritage during the disentailment.

The punctiliousness with which the Marquis wrote down in his diary the distances and measurements of roads, buildings and those between each of the stations of the Stations of the Cross he made in Jerusalem, is consistent with the oral tradition that attributes the institution of the Sevillian Stations of the Cross to the surprise caused in the Marquis of Tarifa by the equivalence of the distances he had taken in the Holy Land between the Praetorium and Golgotha with that between his palace and the shrine of the Cruz del Campo. Thus, like the creation of a relic which, on his death, was inventoried among the goods in his chambers: "...".A ribbon that took the measure of the Holy SepulchreFor posterity, the Way of the Cross that he instituted was literally a spatial transposition from Jerusalem to Seville, as can be deduced from a booklet published in 1653 with the title "...".A very devout memory and a very useful reminder of the laborious road that Christ our Redeemer made to lead us to Glory [...] from the House of Pilate to Mount Calvary [...] The stretch of which is the one that begins from the Houses of the Most Excellent Dukes of Alcala to the Cruz del Campo in this City". and in which it is stated that Don Fadrique ".He traced the measure and distance from the House of Pilate to Calvary and he traced the distance from his Houses (whose doorway he had carved in the manner and design of Pilate's) to the Station of the Cross of the Field so that this most noble City would be ennobled with the devout memory of this place and enjoy the innumerable indulgences that those who visit him in Gerusalemme participate in".

Certainly, like everything related to the reliquary world, this tradition does not stand up to positivist historical criticism, and historiography points out, with accurate erudition, although somewhat irrelevant to understanding Baroque piety, that originally the Way of the Cross did not reach the Cruz del Campo and that the measurements, incongruously taken up to the aforementioned shrine, have nothing to do with those of the Way of the Cross practised in Jerusalem, identifying this with the one carried out by Don Fadrique. The first documentary mention, known to date, of the Cruz del Campo as the end of the itinerary of the Way of the Cross appears in a brief of Pope Urban VIII, dated 14 November 1625, by which he granted plenary indulgence to those who practised this devout exercise, as can be seen in the marble altarpiece that the 3rd Duke of Alcalá ordered to be placed on the façade of his house in memory of this pontifical grace, with an inscription that reads: "The Cross of the Field is the end of the itinerary of the Way of the Cross:

"THIS HOLY CROSS BEGINS THE SEASON AND IN THE CROSS OF THE FIELD THE MOST PLENARY JUBILEE IS WON, PLENARY INDULGENCE FOR ALL SINS, GRANTED TO ALL PERSONS WHO, HAVING CONFESSED AND RECEIVED COMMUNION, DEVOUTLY PRAY BEFORE THE CROSS OF THE FIELD ON THE FRIDAYS OF LENT. THEY MUST HAVE THE BULL OF THE HOLY CRUSADE OF THIS YEAR. THE EXCELLENCY DON FERNANDO AFÁN DE RIVERA Y ENRÍQUEZ, DUKE OF ALCALÁ, ETC. BEING AMBASSADOR EXTRAORDINARY TO GIVE OBEDIENCE TO THE SANCTITY OF URBAN VIII GRANTED HIM THIS JUBILEE AND BEING VICEROY AND CAPTAIN GENERAL OF THE KINGDOM OF NAPLES HE ORDERED THIS HOLY CROSS TO BE DEDICATED IN THIS PLACE TO BEGIN THE SEASON IN THE YEAR MDCXXX."

In any case, with an increasing number of stations, from the initial seven mentioned in the brief of 1529 by which Clement VII granted indulgences to those who made the stations, heirs of the Via Passionis medieval, passing through the twelve mentioned in the aforementioned 1653 booklet, to the fourteen of the mid-18th century, the same as the present-day Stations of the CrossThis act of piety has contributed like few others to shaping the Sevillian sensibility around the commemoration of the Passion of Christ and, for this reason, it is rightly pointed out as one of the sources that shaped the Sevillian Holy Week.

Over time, the path to the Cruz del Campo would be marked by wooden crosses, some on pedestals and others on the walls of the convents or on the arches of the Carmona pipes, crosses that would gradually disappear throughout the 19th century, except for the one that was fixed to house number two in the Plaza de Pilatos, which was moved to the chapel of the Palace, where it is still preserved. This disappearance was a reflection of the decline of a devotional exercise that was not recovered until the fifth decade of the 20th century with the creation of the Pious Union to the Cruz del Campo, an association canonically erected in 1958 by Cardinal Bueno Monreal, at the request of the Duke of Medinaceli and Alcalá, Rafael Medina Vilallonga, whose essential aim is the promotion of the recitation of the Way of the Cross, a subject we deal with in the section dedicated to the work of this pious association, which you can access by clicking on the corresponding section of the related content.