Two of the tapestries, the richest in material and composition, on display at the Hospital de Tavera in Toledo are part of a series, now dispersed, woven on the looms of the Brussels tapestry maker Willem de Pannemaker. The year on the selvage of the first tapestry in the series, 1570, must be the year when work began on the set, which would take at least four years to complete. Thus, with Pannemaker having begun his activity in the third decade of the 16th century and ceased in 1581, this cycle would be a work of maturity of the most famous of the Flemish tapestry makers, supplier of the house of Habsburg and of a few prominent aristocrats of the Hispanic Monarchy, who ended his last decade of work weaving what is - in the words of Concha Herrero Carretero, curator of Tapestries of Patrimonio Nacional, (2010, p. 8) - "a tapestry that is a work of great maturity, a tapestry of great importance for the Spanish monarchy".one of the most beautiful series conceived in the century, comparable or superior to the Poems or Fables of Ovid in the possession of Philip II in 1556, or to the fables of Vertumnus and Pomona acquired by Mary of Hungary before 1548.".

Since the first publication of this series by José Ramón Mélida suggested that it may have been commissioned by Juan de la Cerda, 4th Duke of Medinaceli, during his stay as governor in the Low Countries, the latter has been held to be the commissioner. More recently, on the occasion of her 2010 exhibition at the Prado Museum, Concha Herrero Carretero located in the Medinaceli Archive the oldest known document to date that mentions this cycle: the inventory of his personal property ordered by Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, on the death in 1603 of his wife Catalina de la Cerda, daughter of the aforementioned 4th Duke of Medinaceli. For the author, this document would corroborate Mélida's hypothesis and would allow us to deduce the way in which it entered the collection of the famous valide of Philip III: the dowry of this marriage of the youngest daughter of the 4th Duke of Medinaceli, celebrated in 1576. Despite the plausibility of this conjecture, it should be borne in mind, in addition to the economic and social status of each of the spouses in 1576, that the stay in the Netherlands of the 4th Duke of Medinaceli was limited to a few months in 1572, i.e. with the series begun two years earlier, and that this tapestry is the last entry in the inventory of 1603.

Indicative of the importance attached to this tapestry is, on the one hand, that it was among the few items in the collection of the 1st Duke of Lerma that was passed on to the next generation - the collection was diluted as quickly as it was formed - and passed on to his grandson Francisco, 2nd Duke of Lerma, married to Feliche Enríquez de Cabrera; But, on the other hand, and above all, the fact that this long-lived widowed Duchess of Lerma, who outlived her husband by forty years, wanted to ensure that the most precious and representative asset of the collection inherited by the deceased, these eight tapestries, remained permanently linked to the entailed estate of the House of Lerma, as long as it continued in her descendants. As the said house was, at that time, under a difficult, by rigorous agnation, tenuta lawsuit, he established as a condition that, otherwise, it would become part of the entailed estate of the House of the Major Adelantamiento of Castile, by which means, this tapestry was linked to the patrimony of the House of Medinaceli.

In the will into which the Medinaceli collection was divided, that of the 15th Duke, Luis Tomás Fernández de Córdoba (1813-1873), the series of tapestries was left in a joint ownership that was maintained until 1909 and for which there is no documentation until 1903, the year of the death of Ángela Pérez de Barradas, widowed Duchess of Medinaceli, better known as the Duchess of Denia, who successively occupied the two palaces in which the collection was exhibited during those years: The first was in the Paseo del Prado and the second in the Plaza de Colón, both of which have since disappeared. Of the latter, which she shared with her second husband, Luis de León y Cataumber, some photographs from period magazines have survived, showing part of the series, the three tapestries inherited by the 17th Duke of Medinaceli, hanging on the walls of the room where the armoury of the House of Medinaceli was kept, now in the Museo del Ejército as a testamentary legacy of the Duke himself.

The series was already well known among specialists when, in 1905, it was decided to photograph it in order to make an album, with text and captions by José Ramón Melida, with the aim of publishing it by sending it to various art magazines. Although no copy of this album, which the archaeologist called "The Fables of Mercury"Two articles published under his signature in 1905 (Les Arts Anciens de Flandre, I, pp. 169-171) and 1907 (Forma, vol. II, pp. 262-274) derive from it. In them, he corrects the place of manufacture proposed by the appraisers, noting that they bear the known mark of the Brussels workshops, the double B; he advances the aforementioned hypothesis of a possible commission from the 4th Duke of Medinaceli and slightly alters the order given by the appraisers, although, as he was unable to identify the literary source, he also failed to order it correctly.

In 1963, another archaeologist, Antonio Blanco Freijeiro, recognised the literary source used by the cartoonist who drew the series: the story of the love affair of Mercury and Herse from Book II of Ovid's Metamorphoses. As this story is an allegory of the corruption caused in Aglauro by envy for the beauty of his sister Herse and of the punishment that this deserves, Blanco Freijeiro entitled it Tapestry of Aglauro's fable. Years later, in 1994, Nello Forte Grazzini, analysing another edition of the same subject, of which only three tapestries survive, one of them in the Quirinale, placed the cartoonist in the circle of Giulio Romano in Mantua, whose knowledge of Raphael's work would explain the references to his school. Giovanni Battista Lodi is now proposed as the painter, a native of Cremona but resident in Flanders, "who was born in Cremona but lived in Flanders".He could have directed the execution of the great pictorial models on the basis of the drawings that were sent to him from Mantua."(N. Forte Grazzini, 2010, p. 48).

In 2010, Concha Herrero proposed to name the series ".The wedding of Mercury"as it appears in the Duke of Lerma's inventory of 1607, as it is more expressive than Historia de la fábula de Mercurio, which appears both in the entry of 1603 and in Mélida's first publication. However, as there are three known editions of this marriage and this is not the princely edition, but the first edition has either been lost or was woven by the tapestry maker Dermoyen around 1540 at the latest (Ibid. P. 47), we thought it preferable to title it Lerma-Medinaceli series of the wedding of MercuryThe aim is to record its material history and, at the same time, to distinguish it from the other two editions.

Below, we detail the order of the story as established by Blanco Freijeiro, titling each tapestry according to the aforementioned article by Concha Herrero, mentioning the numbering with which they were drawn by lot, which corresponds to the order in which they were exhibited in the Medinaceli palace in the Plaza de Colón and the title that the appraisers, Guillermo de Osma and his father-in-law, the Count of Valencia de don Juan, gave them in 1903:

-

Mercury in love with Herse: Ovid imagines Mercury as a kite that, flying in circles, becomes increasingly captivated by the beauty of Herse, daughter of the king of Attica, Cecrope, who stands out among the other maidens strolling from the royal fortress. In 1909, under the number 2 and the title of "The walk"It was the property of María del Dulce Nombre Fernández de Córdoba y Pérez de Barradas, Duchess consort of Híjar, and is now on display in the Dueñas Palace in Seville, having been inherited by her great-granddaughter, the 18th Duchess of Alba.

-

Mercury and Herse Promenade: Mercury decides to come down to earth without disguise, confident that his beauty will make Herse fall in love with him. In 1909, under the number 7 and the title of "Two figures"The painting was the property of María del Carmen Fernández de Córdoba y Pérez de Barradas, Countess of Gavia and Valdelagrana, who bequeathed all her assets to the Capuchin order. In 1965 it was acquired by the Museo del Prado. From this bequest also comes another work of art acquired by this museum in 1969: the Equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma of Rubens.

-

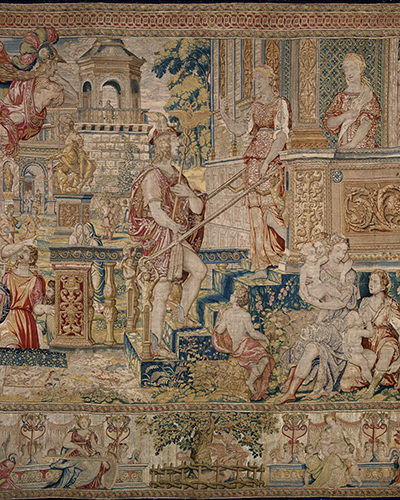

Mercury detained by Aglaurus: Mercury arrives before Aglaurus, another daughter of King Cécrope, who occupied the room next to that of her sister Herse, which Mercury had to pass through to reach her. Aglaurus dares to question the god about her identity and the cause of her coming and he asks for her help "...".so that his aunt's offspring could be named"but Aglauro demands an exorbitant amount of gold in return and fires him, provoking Minerva's anger. In 1909, under the number 4 and the title of "The Staircase"It was inherited by the 17th Duke of Medinaceli and passed to his second daughter, Paz, 16th Duchess of Lerma, and is now owned by her son, Fernando Larios Fernández de Córdoba, Duke of Lerma, who has it on deposit at the Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli.

-

Cecrope welcomes Mercury: This tapestry, together with the present number 6, are precisely those whose subject matter is most consonant with the courtly mentality, and yet the only ones that do not strictly correspond to Ovid's account. Cecrope was the first mythical king of Attica and is here depicted as a magnificent and obsequious monarch and not, as the myth imagined him, in his zoomorphic nature, half-man, half-serpent. To him are attributed the first civilising rules introduced in Athens, including the institution of marriage. But Cecrope is also a father, so his main obligation was to give status to his sons, which, in the case of daughters, translated into procuring them hypergamous marriages, so that to receive properly a god, who intends one of his daughters, would be a natural part of the aristocratic ethos. This tapestry is the one that, in 1934, the widow of Carlos Fernández de Córdoba, 2nd Duke of Tarifa, included in the bequest of part of her collection to the Prado Museum, where it remains. In the 1909 draw it was number 5 entitled "The Canopy" and went to the Duchess of Uceda, who must have swapped it with the one that went to her brother, the Duke of Tarifa.

-

Aglauro corrupted by envy: An enraged Minerva orders Envy to poison Aglaurus with her poison. Although Ovid places this scene in Aglaurus's bed, the cartoonist prefers to set it at a court banquet that the king offers to his divine guest. In 1909, under the number 1 and the title "The dinner"The estate belonged to the 17th Duke of Medinaceli, who left it by inheritance to his third daughter, the 20th Duchess of Cardona, whose lineage continues.

-

Dancing at the Cecrope palace: As we have already noted in number 4, this tapestry has no equivalent in the story of the Metamorphoses and could be in other positions, but Blanco Freijeiro placed it after the banquet, for chronological logic and because the dance would form part of the punishment devised by Minerva to punish Aglauro's pride and avarice: to be devoured by envy on contemplating the happiness of her sister Herse. In 1909, under the number 8 and the title of "The dance"It was the property of the 17th Duke of Medinaceli, from whom it was inherited by his first-born daughter, Victoria Eugenia Fernández de Córdoba, founder of the Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, the institution that acquired it in 2004.

-

Herse bridal chamber: This scene is a vision that Envy places before Aglaurus' eyes: the happy consummation of Mercury's marriage to his sister Herse. In 1909, under the number 3 and the title of "The Bed"It was the property of Fernando Fernández de Córdoba, 14th Duke of Lerma, who quickly sold it to Jacques Seligmann, the most important antiquities dealer of the time, based in Paris and New York, where it was acquired by the banker and collector of Spanish and Italian art, George Blumenthal, patron and seventh president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to whom he bequeathed it in 1941.

-

Metamorphosis of Aglaurus and departure of Mercury: The cartoonist depicted two successive scenes in a single image. On the left, Mercury's punishment of Aglaurus who, corrupted by envy, waits on the threshold of the staircase to prevent the god's entrance, saying to him: "...".I will not move from here until I expel you."and so the god, in keeping with his words, transformed her into stone. On the right, the end of this myth with the flight of the god who, having executed the punishment that Aglaurus' words and sacrilegious soul deserve, flaps his wings and returns to the ether. In 1909, under the number 6 and the title "The reception"This tapestry, which corresponded to the Duke of Tarifa, must have been exchanged for number 5 with his sister, the widowed Duchess of Uceda, possibly because she was considerably younger. This tapestry followed the same path as the previous one.