Main courtyard

15th century: A U-shaped porticoed courtyard

The beauty and uniqueness of this main courtyard, which is the core of the palace and the only articulating element of the whole complex.is based on its intense stylistic diversity. A harmonious synthesis of Gothic, Mudejar, Renaissance and Romanesque elements, its present-day appearance is the product of successive interventions from the end of the 15th century to the mid-19th century.

The primitive late 15th century courtyardthe Pedro Enríquez and Catalina de RiberaIt must have been quadrangular, although it was only porticoed on three sides, with galleries that can be distinguished by the smooth conical capital on which its arches rest.

1526: The Renaissance intervention

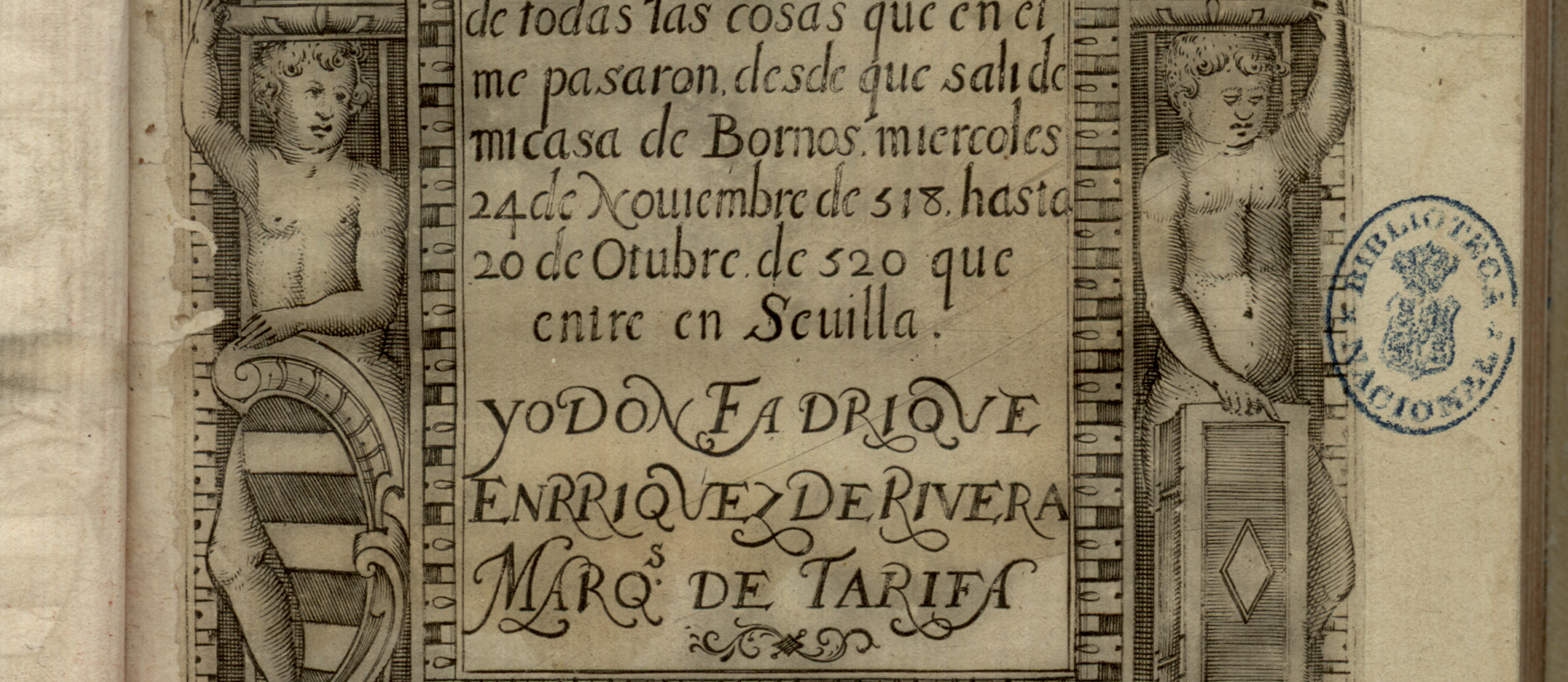

The first documented intervention in the palace of his son Don Fadrique was carried out in 1526 to complete, with a new portico, the courtyard on the east side, an operation in which he broadly respected the guidelines established by his mother, with the exception of the modification of the type of base and capital, in which he opted for a The basis of the so-called "claw" basis and for a capitel "de moñasBoth of these elements were to enjoy extraordinary fortune, being used in the majority of Sevillian courtyards from the Renaissance onwards.

Also, in the new gallery, the Marqués de Tarifa maintained one of the constants of the courtyard which is the disparity in the size of their arches, ranging from a little more than two metres to three and a half metres in span. One of the possible explanations for this irregularity, which is certainly more pronounced in the pandas of the medieval palace, is that mudejar architecture inherited from Islamic art the tendency to stand outframing them with a larger arch, the entrances to the rooms that open onto the galleries.

He did, however, modify the decoration of the walls by covering them with towering tiled skirting boards and changed the medieval central fountain - whose existence is only known to us through a brief mention by an anonymous Milanese merchant who travelled to Seville in 1517 - for the present fountain, with an octagonal floor plan, carved in Carrara marble, once topped by a satyr and, today, by the double face of the god Janus, a sculpture from the collection of the 1st Duke of Alcalá. This source was acquired by the 1st Marquis of Tarifa in Genoa.in 1528, in the same workshop where he had commissioned, among many other marble pieces, the front of the palace and the graves of their parents for the Cartuja de las Cuevas, pantheon of the House of Ribera.

1570: The sculptural programme

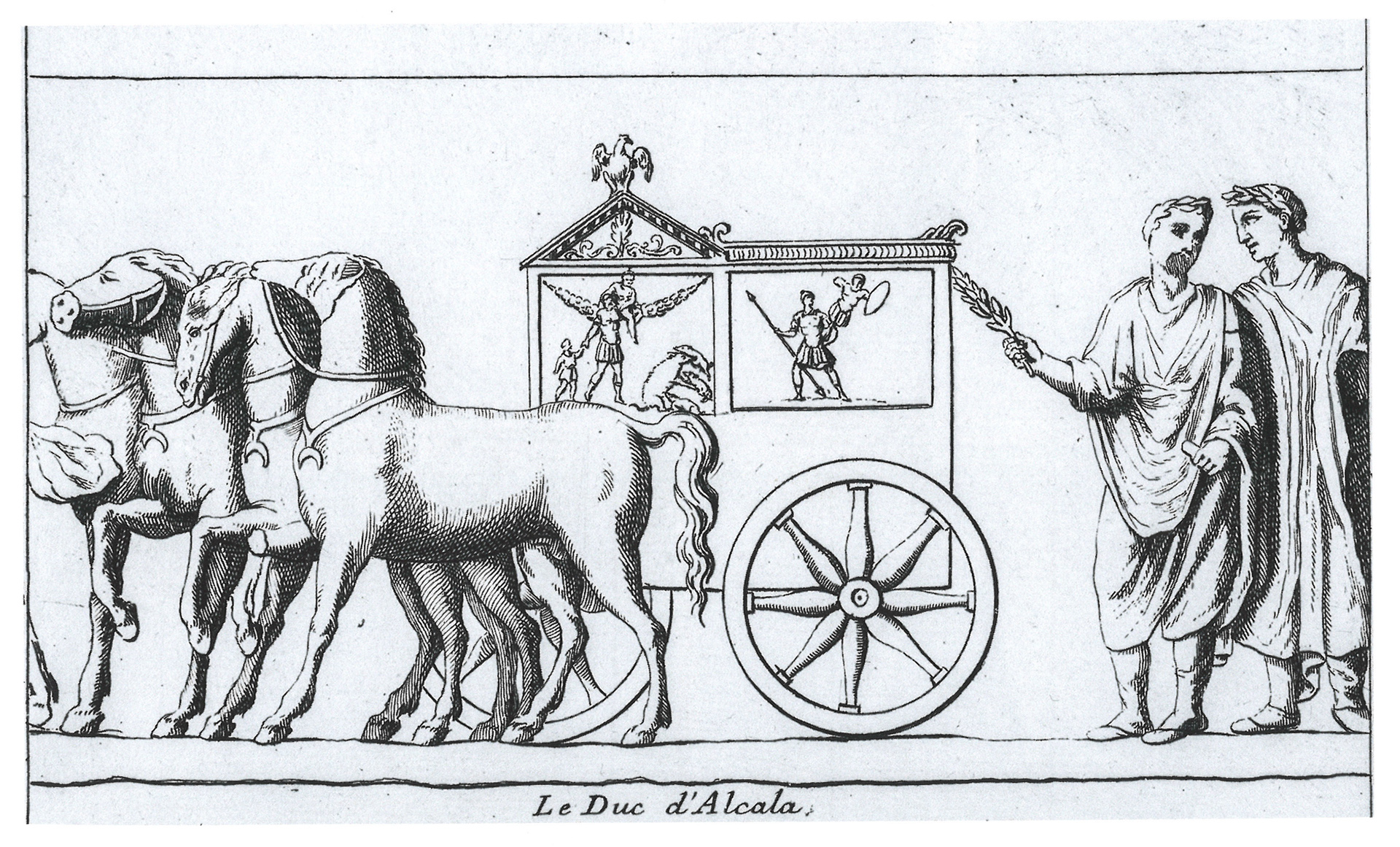

Perhaps the most important aesthetic transformation of the courtyard was carried out by his nephew and heir, Per Afan de Riberaby sending from Naples, around 1570, a huge and varied sculptural collection The main pieces, which are much larger than life-size, were used to enrich the four corners of the courtyard, and twenty-four of the busts were placed in tondos around the perimeter of the galleries.

19th century: the Romantic reforms

The courtyard remained unaltered for almost three centuries, as it was not intervened on again until the mid-19th century. The reasons for this long parenthesis are to be found in the secondary character of the palace from the mid-17th century onwards, due to the change of owners and tastes. Only with the rediscovery of the Mudejar by romantic travellerswhich once again place this palace as an obligatory stop on the circuits of cultured EuropePilate's House will be given a new lease of life.

Since the middle of the 19th century, the fifteenth Duke and Duchess of Medinaceli spent long periods of time each year in this palace, devoting themselves to their restoration within the parameters of Romantic picturesqueness. The Duchess of Medinaceli, Doña Angela Pérez de Barradas, better known by the title she obtained during her widowhood, played a special role in this process, Duchess of DeniaIn the 1850s and 60s he introduced important novelties such as the opening of an entrance in the centre of the courtyard, in keeping with the 19th century taste for open courtyards - but breaking with the Islamic tradition, inherited from the Mudejar, of entrances on a broken axis -; the replacement of the original clay floor with new black and white marble flooring and the installation, in the windows of the lower galleries, of new pseudo-Nazarite mullioned windows.